Open Access

Open Access

Linking proactive personality to strengths use: The mediator of psychological safety and the moderator of exploitative leadership

1 Business School, Beijing Wuzi University, Beijing, 101149, China

2 School of Economics and Management, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, 102206, China

* Corresponding Author: Yang Liu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 43-49. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065880

Received 11 August 2024; Accepted 20 December 2024; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

Drawing upon the Conservation of Resources theory, this study investigated the relationship between proactive personality and strengths use, as well as the mediating role of psychological safety and the moderating role of exploitative leadership within this relationship. Data were collected from 368 employees (females = 57.61%; mean age = 32.35; SD = 6.31) working in various organizations in China at two points in time with a two-week interval. We conducted structural equation modeling and a moderated mediation path analysis to test our hypotheses. The results demonstrated that proactive personality is positively related to strengths use and psychological safety partially mediates the association of proactive personality and strengths use. Furthermore, this study also found that exploitative leadership weakens the direct relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety and the indirect relationship of proactive personality with strengths use through psychological safety. This study identified the underlying mechanisms between proactive personality and strengths use.Keywords

In the past two decades, the development of positive psychology has sparked interest in positive psychological traits and states, emphasizing the in-depth study of human strengths and virtues (Kashdan et al., 2022). Exploring how to stimulate employees’ potential and promote their personal strengths use has become a significant topic in organizational management research (Ding & Yu, 2021). Strengths use can not only improve work efficiency but also increase personal performance and job satisfaction (Lavy & Littman-Ovadia, 2017). Thus, scholars call for understanding and exploring the antecedents that affect employees’ strengths use (Kong & Ho, 2016), which holds crucial practical significance for enterprise management. Personality is a key factor affecting individuals’ behaviors, a narrow stream of research has examined the link between proactive personality and strengths use (van Woerkom et al., 2016). However, the underlying mechanisms related to the proactive personality and its strengths use remain largely unexplored. This study explores why and when proactive personality may influence employees’ strengths use.

Proactive personality and strengths use

Proactive personality refers to a trait-level inclination to actively create change in the environment (Yi-Feng Chen et al., 2021). Previous studies have confirmed that proactive personality is a unique individual trait with distinct predictive capabilities (Young et al., 2018). Strengths use refers to a person’s unique characteristics and abilities, which inspire vitality and lead to optimal performance (Wood et al., 2011). The link between proactive personality and strengths use is based on the specific characteristics of proactive individuals. First, proactive individuals possess strong intrinsic motivation and tend to take proactive actions to influence and change their environment (Parker et al., 2010). This implies that they can recognize opportunities and threats in their environment and proactively seek and leverage opportunities to achieve their goals (Ilies et al., 2005). During this exploration process, individuals are more likely to identify and harness their strengths.

Second, strengths use can be considered a job-related motivational resource as it facilitates achieving work goals, such as higher performance and lower absenteeism (Yi-Feng Chen et al., 2021). According to COR theory, individuals with more resources are more likely to acquire additional resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Hence, Proactive individuals (personal resources) are more likely to utilize their strengths (motivational resources) at work. Previous limited research has established a positive direct relationship between proactive personality and strengths use (Frazier et al., 2017). For instance, research by Yi-Feng Chen et al. (2021) also supports a positive correlation between proactive personality and perceived strengths use among healthcare professionals during the pandemic.

Psychological safety as a mediator

Psychological safety is defined as the sense of being able to express oneself without fear of negative consequences for self-image, status, or career (Lyu, 2016). Individuals with high psychological safety can safely share opinions and creative ideas and provide constructive criticism (Newman et al., 2017). Existing research has shown that psychological safety is positively related to job engagement, team and individual performance, and creative behaviors (Frazier et al., 2017). Certainly, some scholars have investigated the significant antecedents of psychological safety. Among these, individual differences are also considered important factors influencing psychological safety. For example, May et al. (2004) explored how self-consciousness can affect psychological safety.

We refer to the COR theory to explain the mediating role of psychological safety. The upward spiral of resources hypothesis suggests that individuals who possess resources are more likely to acquire additional resources, leading to beneficial outcomes for the organization (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Proactive personality, as a type of trait resource, is more likely to accumulate psychological resources, leading to behaviors beneficial to the individual and the organization (e.g., strengths use). Proactive individuals tend to have a stronger sense of psychological safety. This is because they often take action, influence their environment, and proactively identify opportunities and solve problems (Crant, 2000). They generally possess higher confidence and intrinsic motivation, allowing them to continuously acquire new resources like information, social support, and a sense of control (Yang et al., 2011). They tend to build open and trusting environments, leading to a greater sense of safety in their surroundings compared to those without a proactive personality. Previous studies have also confirmed the positive relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety (Elsaied, 2018).

Conversely, psychological safety can provide the basis for strengths use. According to the Johari Window, individuals may hide their strengths from themselves or others (Luft & Ingham, 1961). As psychological safety increases, trust within the group also strengthens, and individuals’ behaviors, motivations, and resources are revealed and available for group use. Existing research has shown that psychological safety can enhance the identification and utilization of employee strengths (Ferguson, 2021).

The moderating role of exploitative leadership

Exploitative leadership is a highly self-centered style that seeks personal gains at the expense of others (Schmid et al., 2017). It has attracted widespread attention from scholars as an emerging destructive leadership topic. Schmid et al. (2017) identified five dimensions of exploitative leadership, namely genuine egoistic behaviors, taking credit, exerting pressure, undermining development and manipulating. Genuine egoistic behaviors refer to leaders who prioritize their interests and view subordinates as means to achieve personal gains. Taking credit captures that leaders unfairly claim the hard work or achievements of their subordinates as their own. Exerting pressure means leaders impose unnecessary and excessive pressure on employees to force them to complete tasks. Undermining development means leaders continuously assign tedious and boring tasks to employees and hinder their career development. Manipulating describes that leaders achieve their goals by sowing discord among subordinates to benefit themselves. Existing research has demonstrated the negative effects of exploitative leadership on employees, such as decreased job satisfaction, increased turnover intention, and perceived social exchange imbalance (Pircher Verdorfer et al., 2019; Schmid et al., 2018).

As a form of destructive leadership, it serves as a negative workplace stressor and a resource-depleting leadership (Schmid et al., 2017). Exploitative leaders naturally assume that others exist to serve them, which threatens personal dignity (Guo et al., 2020). It is well known that leader support is one of the most valuable social resources in the workplace (Lee et al., 2018). Exploitative leadership seldom offers guidance or learning opportunities to employees, impeding their professional growth and career development (Schmid et al., 2017), and potentially causing a resource loss related to job control and autonomy (Guo et al., 2020).

According to the COR theory, when employees experience actual or potential resource loss, they are more likely to adopt defensive strategies to protect themselves from further loss (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Individuals have a stronger sensitivity to resource loss compared to resource gain. In the context of exploitative leadership, where personal interests are prioritized over employee needs and career growth, employees may feel that their personal resources are drained without any return, resulting in extra stress (Guo et al., 2023). Proactive individuals in such a context may perceive self-expression as an interpersonal risk that could lead to negative outcomes such as unfair treatment. In fact, when the work environment does not provide a supportive atmosphere, their intrinsic motivation may diminish (Gagné & Deci, 2005). To avoid further resource exploitation, these employees may adopt avoidance or defensive measures to suppress their proactivity (trait resources) and reduce risk-taking. Consequently, exploitative leadership weakens the positive impact of proactive personality on employees’ psychological safety.

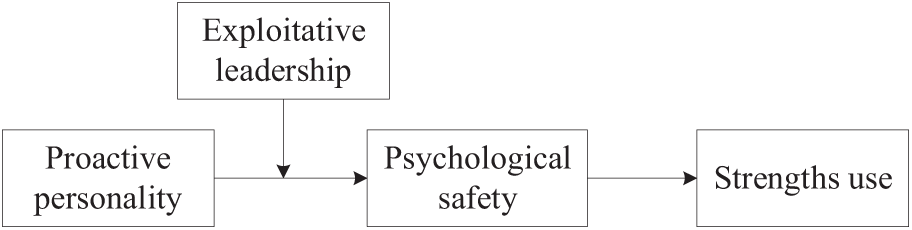

We examined the roles of psychological safety and exploitative leadership in the relationship between proactive personality and strengths use. Figure 1 shows our research model. To achieve this goal, we tested the following four hypotheses:

Figure 1. The proposed conceptual model

• Hypothesis 1: Proactive personality has a positive association with strengths use.

• Hypothesis 2: Psychological safety mediates the relationships between proactive personality and strengths use.

• Hypothesis 3: Exploitative leadership weakens the relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety.

• Hypothesis 4: The indirect relationship between proactive personality and strengths use via psychological safety is negatively moderated by exploitative leadership.

Credamo has been regarded as one of the most important options for researchers conducting surveys in China. The platform is an intelligent and professional survey platform, with registered users covering all provinces and cities in China. We recruited participants for an online questionnaire survey through the Credamo platform between January and February 2024. The participants in this survey were registered users of the platform, from different provinces, cities, and companies. We selected currently employed workers for the survey. All participants were informed that the questionnaire was solely for academic purposes, and its content would be kept anonymous and confidential. Furthermore, participation was entirely voluntary, and they could withdraw from the survey at any time. To avoid common method bias, we conducted two rounds of data collection with a two-week interval.

In Stage 1, participants completed questionnaires concerning the independent variable (proactive personality), the moderating variable (exploitative leadership), and demographic information. A total of 467 questionnaires were collected in this phase, and after excluding those with too short or too long response times, 424 valid questionnaires were retained. In Stage 2, participants completed the questionnaires for the mediator variable (psychological safety) and the outcome variable (strengths use). The Credamo platform assigns a unique identifier (ID) to each user, which we used to match the data from the two phases. The design of our survey prevented participants from skipping questions or declining to answer the questionnaire. A total of 368 questionnaires were collected in Phase 2. The demographic analysis indicated that males constituted 42.39% of the participants, 94.57% possessed a bachelor’s degree or higher, the average age was 32.35 years (SD = 6.31), and the mean organizational tenure stood at 8.57 years (SD = 6.20).

The study employed a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree” to measure all variables. To adapt the original all variables English scales to the Chinese context, a translation-back-translation procedure (Brislin, 1970) was adopted to ensure semantic equivalence.

Proactive personality was evaluated with a 10-item scale used by Seibert et al. (1999). Sample items included statements such as “I am always looking for better ways to do things” and “I can spot a good opportunity long before others can”. The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was 0.86.

We measured exploitative leadership with 15 items from Schmid et al. (2017). An example item is “My leader takes it for granted that my work can be used for his or her personal benefit”. In the current study, Cronbach’s of the exploitative leadership scale was 0.96.

We measured psychological safety with 7 items scale used by Edmondson (1999). An example item is “It is safe to take a risk on this team”. Cronbach’s of the psychological safety scale was 0.77.

Strengths use was measured employing a 5-items scale used by Ding et al. (2023). An example items for this scale is “I seek opportunities to do my work in a manner that best suits my strong points”. Cronbach’s of the strengths use scale was 0.76.

In line with the research by Kong and Ho (2016), we controlled for employee gender and organizational tenure.

Our procedures involving human participants comply with institutional and/or national research committee ethical standards, as well as the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants were voluntary.

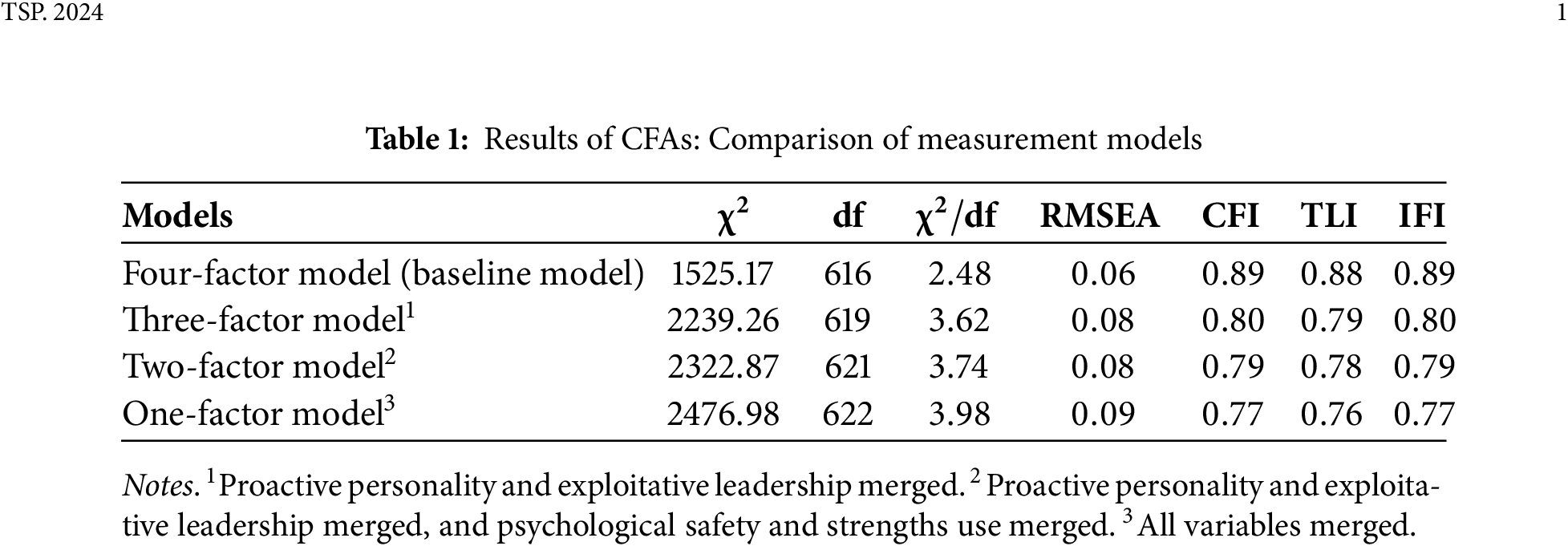

We employed structural equation modeling analysis with bootstrapping analysis (resampling 5000) and utilized 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to examine our hypotheses. Consistent with previous studies, CFA was undertaken to examine the discriminant validity of the main research variables. As displayed in Table 1, the result showed that the four-factor measurement model exhibited a better data fit compared to alternative measurement models.

Considering the self-report research and cross-sectional survey design, there was a potential common method bias (CMB) to arise. To reduce this, we adopted the procedure control and statistics control strategies recommended by Podsakoff et al. (2003). Procedurally, data were collected at two distinct time points separated by a two-week interval. Statistically, a latent common method factor was created and loaded on all items of proactive personality, exploitative leadership, psychological safety, and strengths use. Results demonstrated that the five-factor measurement model comprising the method factor and four research variables does mot exhibits a better fit to the data ( = 1495.79, df = 615, = 2.43, RMSEA = 0.06, CFI = 0.89, TLI = 0.88, IFI = 0.89). Consequently, the present study did not exist significantly common method bias.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analyses

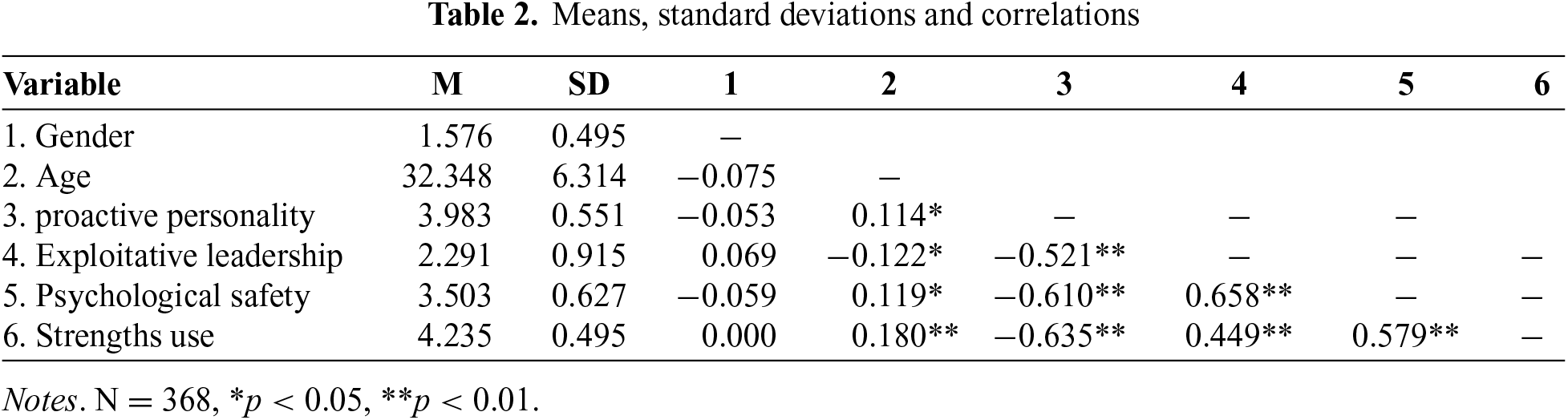

Table 2 reported the means, standard deviations, and correlations of research variables. The result of correlation analyses underscored that proactive personality is positively related to psychological safety (r = 0.61, p < 0.01), strengths use (r = 0.64, p < 0.01), psychological safety is positively related to strengths use (r = 0.58, p < 0.01). Exploitative leadership is negatively correlated with psychological safety (r = −0.66, p < 0.01) and strengths use (r = −0.45, p < 0.01).

Proactive personality and strengths use

To examine these hypotheses, we used the structural equation modeling (SEM) to assess the mediational effect, as well as conditional effect and the moderated mediating effect based on 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CI) with 5000 iterations in AMOS. Hypothesis 1 postulated that proactive personality has a positive association with strengths use. SEM with gender, tenure, proactive personality and strengths use was established. Analytical results indicated that this model fits the data very well ( = 5.309, df = 3, = 1.77, RMSEA = 0.046, CFI = 0.98, TLI = 0.97, IFI = 0.98). The path coefficient between proactive personality and strengths use was significant (estimate = 0.57, 95% CI: [0.46, 0.68]). There-fore, Hypothesis 1 received support.

We used moderated mediating SEM to examine Hypothesis 2, 3, and 4. Results of the moderated mediation model showed an adequate fit to the data ( = 13.79, df = 11, = 1.25, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.99 and TLI = 0.99, IFI = 0.99). The direct path coefficients were displayed in Figure 2. The indirect relationship of proactive personality with strengths use via psychological safety was significant (estimate = 0.12, 95% CI: [0.08, 0.18], p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2. Because the direct relationship between proactive personality and strengths use was significant (estimate = 0.40, 95% CI: [0.28, 0.54]) after introducing psychological safety as a mediator, psychological safety partially mediates the relationship of proactive personality with strengths use.

Figure 2. The results of the moderated mediating path analysis. Notes. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

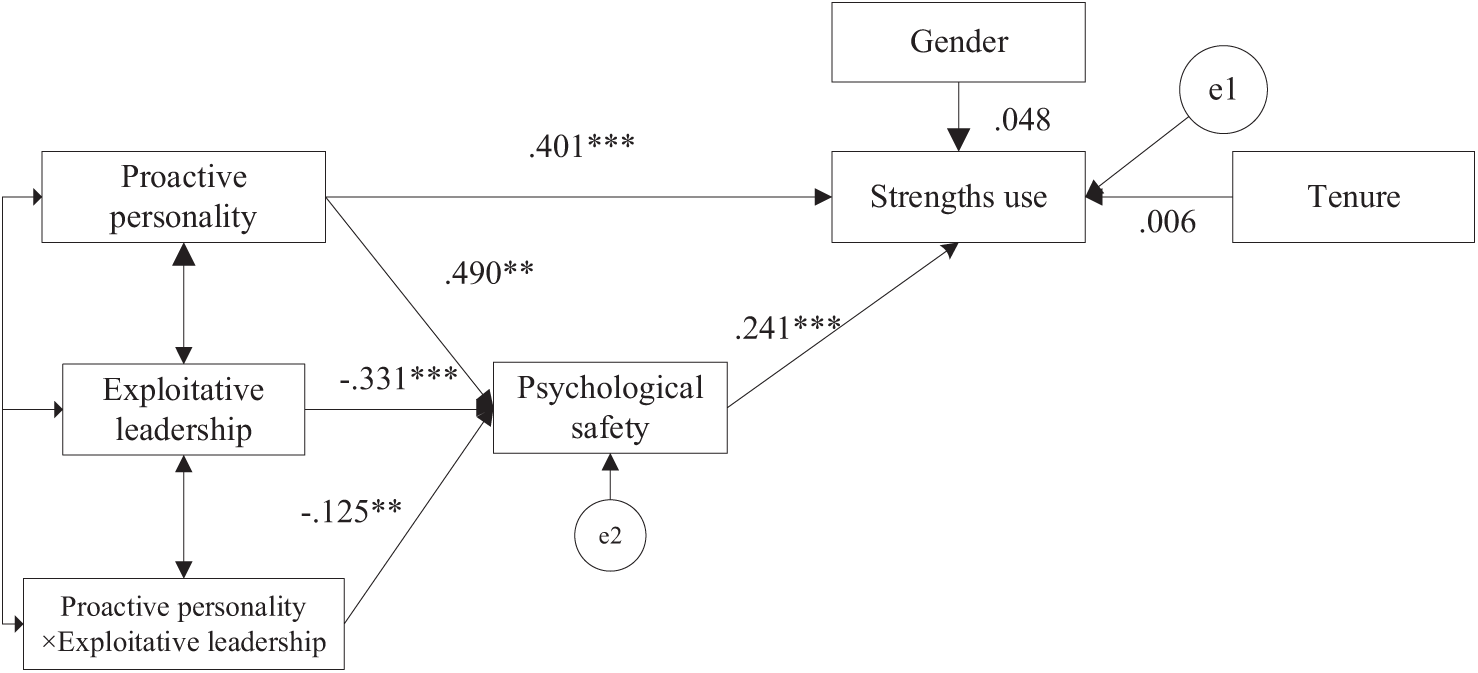

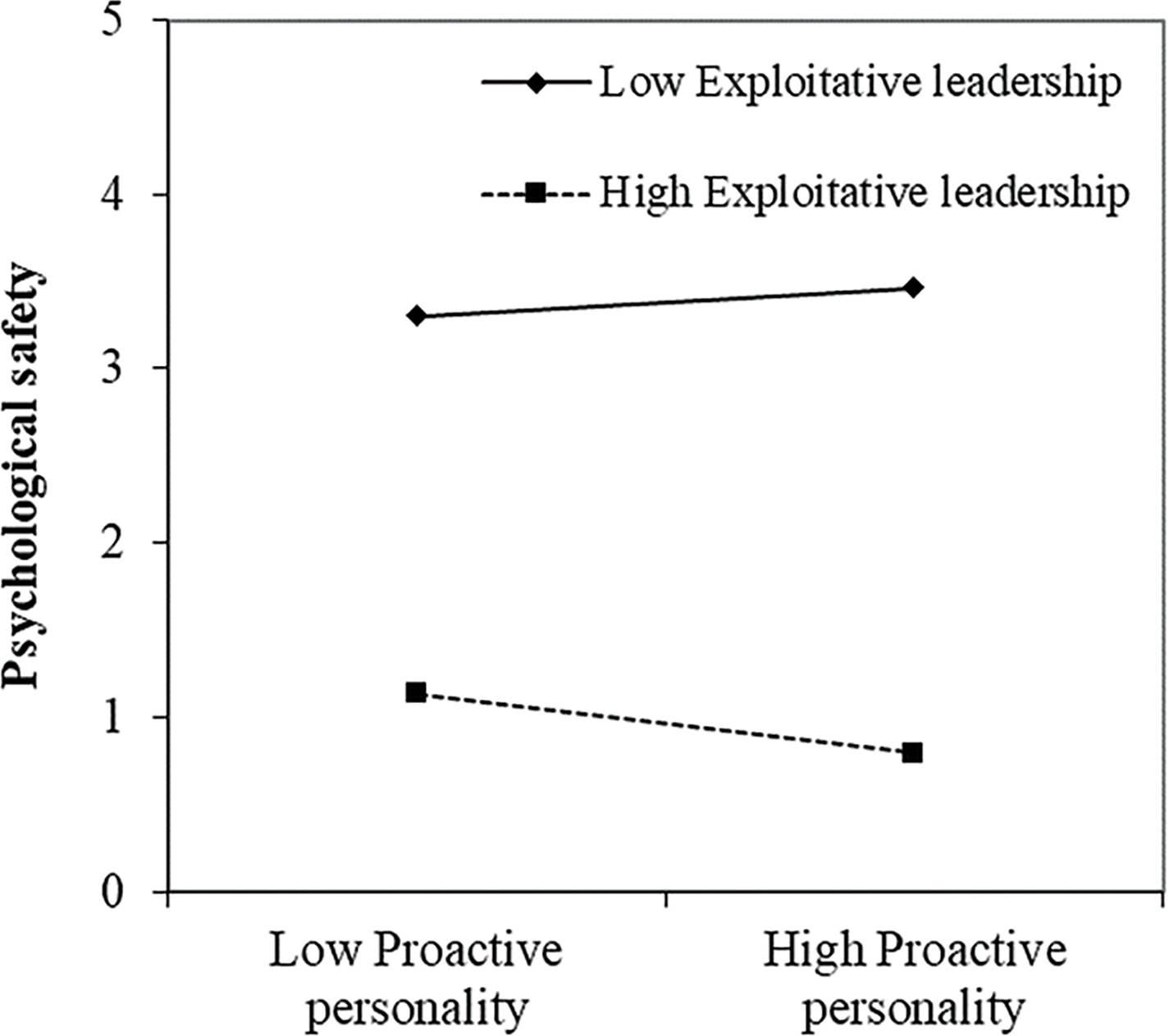

Hypothesis 3 postulated that exploitative leadership weakens the relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety. The interaction term was significant (estimate = −0.13, 95% CI: [−0.21, −0.03]). To further elucidate this interaction effect, the interaction plot of proactive personality and exploitative leadership on psychological safety was depicted in Figure 3, and we also conducted simple slope analysis. Results revealed a stronger positive relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety when exploitative leadership is low (estimate = 0.32, CI: [0.15, 0.46]) than high (estimate = 0.20, CI: [0.02, 0.41]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 received support from data.

Figure 3. Moderation graph of proactive personality and psychological safety

Hypothesis 4 proposed that exploitative leadership weakens the indirect relationship of proactive personality with strengths use through psychological safety. The moderated mediation effect was significant (estimate = −0.03, p < 0.01, 95% CI: [−0.06, −0.01]. Further, the indirect relationship of proactive personality with strengths use via psychological safety was stronger when exploitative leadership was low (estimate = 0.08, 95% CI: [0.05, 0.11]) than high (estimate = 0.05, CI: [0.01, 0.10]). Therefore, Hypothesis 4 received support from data.

This study investigated 368 employees across various organizations, exploring the relationship between proactive personality and strengths use, the mediating effect of psychological safety, and the moderating role of exploitative leadership in this relationship. All hypotheses were confirmed by the research data. Our research results offer multiple theoretical contributions and practical implications.

First, the results of this study indicate a positive relationship between proactive personality and strength use. This finding can be explained by the logic that individuals with more resources are more likely to acquire additional resources (Hobfoll et al., 2018). Proactive individuals create opportunities to leverage their proactivity to generate work-related motivational resources (e.g., strength use). This finding aligns with prior studies. For example, Yi-Feng Chen et al. (2021) reported that proactive personality positively correlates with perceived strength use among healthcare professionals. This research further substantiates the stability of this positive link via empirical evidence in organizational contexts.

Second, this study found that psychological safety mediates the positive linkage between proactive personality and strength use. This result can be interpreted using the COR theory. Specifically, proactive personality serves as a trait resource that activates employees’ psychological resources (e.g., psychological safety), thus promoting their strengths use. This also responds to the call by Newman et al. (2017), encouraging researchers to integrate the perspective of COR theory to fully understand the formation of psychological safety and its impact on workplace outcomes. While prior studies have confirmed the positive association between proactive personality and strengths use, the underlying mechanism remains underexplored. This research pioneers the inclusion of psychological safety as a mediator, shedding light on how proactive personality effectively impacts strengths use. Therefore, this study provides an important contribution to understanding why and how proactive personality influences strengths use.

Third, we found that exploitative leadership significantly negatively moderates the relationship between proactive personality, psychological safety, and strengths use. The COR theory provides an important theoretical foundation for this finding. Specifically, when followers experience resource loss due to exploitative leadership, they tend to conserve proactive resources rather than converting trait resources into psychological resources, and subsequently into strength use. Previous studies have highlighted that resources provided by leaders play a critical role in facilitating or hindering employees’ proactive efforts and proactivity (Wei et al., 2021). Our study provides evidence for this argument by explaining the negative moderating role of exploitative leadership, a destructive leadership style, on the relationship between proactive personality, psychological safety, and strengths use. Moreover, most current studies focus on the negative impacts of exploitative leadership, such as knowledge hiding and psychological stress (Guo et al., 2020; Majeed & Fatima, 2020), while overlooking its potential moderating effects on individual trait utilization. This study extends the theoretical scope of exploitative leadership by uncovering its unique role in the trait-psychology-behavior pathway.

Implications for research and practice

This research holds three key practical implications. First, this study suggests that focusing on employees’ individual traits is an effective strategy for enhancing job performance. Proactive personality, as a trait resource, can promote positive behaviors (such as strengths use) by enhancing individuals’ psychological safety (psychological resource). Organizations should pay attention to individual traits in the recruitment and selection process, giving priority to those who demonstrate proactive personality traits. Moreover, companies should offer personalized development plans and training to help employees identify and utilize their strengths, enhancing job satisfaction and overall performance.

Second, this study emphasizes the importance of creating a work environment that fosters psychological safety in promoting strengths use. Companies should design and implement organizational cultures and policies that boost psychological safety. Specific measures include providing transparent communication channels, establishing positive feedback mechanisms, and encouraging teamwork and innovation. These initiatives can strengthen psychological safety, which in turn boosts their work motivation and performance.

Third, avoiding exploitative leadership styles is a crucial approach to enhancing psychological safety and strengths use. Exploitative leadership weakens the positive impact of proactive personality on psychological safety, thereby affecting strengths use. Organizations should avoid exploitative leadership styles in the selection and training of leaders, promoting and nurturing more supportive leadership (Majeed & Fatima, 2020). By offering leadership development programs and training, companies can help leaders recognize the impact of their behavior on psychological safety and job performance, thereby shaping positive leadership styles.

Limitations and future research directions

This research also has its limitations and constraints. First, the cross-sectional design of this study limits the inference of causal relationships between proactive personality, psychological safety, and strengths use. Future studies should consider employing longitudinal research to establish causality and gain a better understanding of the dynamic interactions among these variables over time.

Second, the data in this study came from a single source, which may raise concerns about common method bias. Although statistical controls were employed to mitigate this issue, future research should use multiple data sources, such as evaluations from supervisors and colleagues, to enhance the robustness of the findings.

Third, this study found that exploitative leadership weakens the positive impact of proactive personality on psychological safety. This result is likely related to the Chinese cultural context. The characteristics of respecting authority and high tolerance in Chinese culture may lead employees to be more inclined to suppress their proactive personality when facing exploitative leadership (Lin et al., 2013). Future research should further explore the generalizability of this result in other cultural contexts and delve into the role of cultural factors in this process. Through cross-cultural research, a more comprehensive understanding of the impact of exploitative leadership on the relationship between proactive personality and psychological safety can be achieved, providing more universally applicable theoretical support for global organizational management practices.

This study reveals the underlying mechanisms between proactive personality and strengths use in the Chinese context, as well as the moderating role of exploitative leadership. The findings suggest that psychological safety acts as a mediator in the relationship between proactive personality and strengths use. When the level of exploitative leadership is high, proactive personality is suppressed, resulting in decreased psychological safety and consequently, reduced strengths use. This research not only deepens the understanding of proactive personality and exploitative leadership but also offers important practical insights for managers on how to effectively boost employees’ strengths use.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the employees who participated in this study.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by Youth Foundation of Beijing Wuzi University (Grant No. 2024XJQN26).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Yang Liu conceived and designed the study and carried out data collection; Zhijie Xu conducted the analysis and interpretation of results; Wenyin Yang drafted the manuscript and obtained research funding. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from YL (y5489264@163.com), upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The research conducted in this study was approved by the Research Institute of Beijing Wuzi University. All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its subsequent amendments or comparable ethical standards. All participants provided voluntary informed consent after being fully informed of the study’s purpose, procedures, and their right to withdraw at any time without consequence.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ding, H., & Yu, E. (2021). Followers’ strengths-based leadership and strengths use of followers: The roles of trait emotional intelligence and role overload. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110300 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ding, H., Yu, E., & Liu, J. (2023). Professional commitment matters! Linking employee strengths use to organizational citizenship behavior. Current Psychology, 43(5), 4505–4515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04515-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383. https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Elsaied, M. M. (2018). Supportive leadership, proactive personality and employee voice behavior: The mediating role of psychological safety. American Journal of Business, 34(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJB-01-2017-0004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ferguson, D. C. (2021). Revealing hidden strengths at work: Unleashing your employees’, stakeholders’, and organization’s greatest potential [Doctoral dissertation]. USA: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12183 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(4), 331–362. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.322 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, L., Cheng, K., & Luo, J. (2020). The effect of exploitative leadership on knowledge hiding: A conservation of resources perspective. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 42(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-03-2020-0085 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, L., Luo, J., & Cheng, K. (2023). Exploitative leadership and counterproductive work behavior: A discrete emotions approach. Personnel Review, 53(2), 353–374. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-02-2021-0131 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. -P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ilies, R., Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2005). Authentic leadership and eudaemonic well-being: Understanding leader-follower outcomes. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(3), 373–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2005.03.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., & Goodman, F. R. (2022). Evolving positive psychology: A blueprint for advancing the study of purpose in life, psychological strengths, and resilience. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.2016906 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kong, D. T., & Ho, V. T. (2016). A self-determination perspective of strengths use at work: Examining its determinant and performance implications. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1004555 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lavy, S., & Littman-Ovadia, H. (2017). My better self: Using strengths at work and work productivity, organizational citizenship behavior, and satisfaction. Journal of Career Development, 44(2), 95–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845316634056 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, S., Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2018). A moderated mediation model of the relationship between abusive supervision and knowledge sharing. The Leadership Quarterly, 29(3), 403–413. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, W., Wang, L., & Chen, S. (2013). Abusive supervision and employee well-being: The moderating effect of power distance orientation. Applied Psychology, 62(2), 308–329. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00520.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Luft, J., & Ingham, H. (1961). The johari window. Human Relations Training News, 5(1), 6–7. [Google Scholar]

Lyu, X. (2016). Effect of organizational justice on work engagement with psychological safety as a mediator: Evidence from China. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 44(8), 1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2016.44.8.1359 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Majeed, M., & Fatima, T. (2020). Impact of exploitative leadership on psychological distress: A study of nurses. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1713–1724. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521–535. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Parker, S. K., Bindl, U. K., & Strauss, K. (2010). Making things happen: A model of proactive motivation. Journal of Management, 36(4), 827–856. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310363732 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pircher Verdorfer, A., Belschak, F. D., & Bobbio, A. (2019). Felt or thought? Examining distinct mechanisms of exploitative leadership and abusive supervision. Academy of Management Proceedings, 2019(1), 18348. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2019.18348abstract [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. -Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmid, E. A., Pircher Verdorfer, A., & Peus, C. V. (2018). Different shades—Different effects? Consequences of different types of destructive leadership. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 438. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schmid, E. A., Verdorfer, A. P., & Peus, C. (2017). Shedding light on leaders’ self-interest: Theory and measurement of exploitative leadership. Journal of Management, 45(4), 1401–1433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317707810 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Seibert, S. E., Crant, J. M., & Kraimer, M. L. (1999). Proactive personality and career success. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84(3), 416–427. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.84.3.416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

van Woerkom, M., Mostert, K., Els, C., Bakker, A. B., de Beer, L., & Rothmann Jr., S. (2016). Strengths use and deficit correction in organizations: Development and validation of a questionnaire. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 25(6), 960–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2016.1193010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wei, Z., Li, C. -J., Li, F., & Chen, T. (2021). How proactive personality affects psychological strain and job performance: The moderating role of leader-member exchange. Personality and Individual Differences, 179(3), 110910. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110910 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wood, A. M., Linley, P. A., Maltby, J., Kashdan, T. B., & Hurling, R. (2011). Using personal and psychological strengths leads to increases in well-being over time: A longitudinal study and the development of the strengths use questionnaire. Personality and Individual Differences, 50(1), 15–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.08.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, J., Gong, Y., & Huo, Y. (2011). Proactive personality, social capital, helping, and turnover intentions. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 26(8), 739–760. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941111181806 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yi-Feng Chen, N., Crant, J. M., Wang, N., Kou, Y., Qin, Y., et al. (2021). When there is a will there is a way: The role of proactive personality in combating COVID-19. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106(2), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Young, H. R., Glerum, D. R., Wang, W., & Joseph, D. L. (2018). Who are the most engaged at work? A meta-analysis of personality and employee engagement. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 39(10), 1330–1346. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2303 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools