Open Access

Open Access

Intentional self-regulation and peer relationship in the teacher-student relationship for learning engagement: A moderation–mediation analysis

1 Wellbeing Research Centre, Faculty of Social Sciences and Liberal Arts, UCSI University, No. 1, Jalan Menara Gading, UCSI Heights (Taman Connaught), Cheras, Kuala Lumpur, 56000, Malaysia

2 Nanjing Institute of Technology, Nanjing, 211167, China

* Corresponding Authors: Mengjun Zhu. Email: ; Xing’an Yao. Email:

# These two authors are co-first authors

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 83-90. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065784

Received 17 April 2024; Accepted 19 January 2025; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the role of intentional self-regulation and the moderating role of peer relationship in the relationship between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement. The study sample comprised 540 Chinese senior secondary school students between the ages of 15–18 (51.67% boys; Mage = 16.56 years; SDage = 0.90). They completed surveys on the Teacher-Student Relationship Scale, the Selection, Optimization, and Compensation (SOC) Scale, the Peer Relationship Scale for Children and Adolescents, and the Learning Engagement Scale. The results following regression analysis showed that teacher-student relationship predicted higher learning engagement among senior secondary school students. Intentional self-regulation partially mediated the link between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement for higher learning engagement. Peer relationship moderated the relationships between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement and moderated the relationship between teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation for higher learning engagement. These findings imply learning engagement can be enhanced by optimizing teacher-student relationship and strengthening intentional self-regulation interventions.Keywords

Adolescents may experience excessive academic burdens which diminish their confidence in learning engagement (Sang et al., 2018). This would be particularly true of the high school phase with its immense academic and examination pressures, necessitating substantial energy investment in learning activities (Rahman et al., 2018). Learning engagement is a key facilitator within school success and completion, serving as a protective factor against student alienation, academic failure, withdrawal, behavioral issues, and even dropout (Zhen et al., 2018). However, intentional self-regulation in adolescents and their peer relationships may explain their teacher-student relationship and sense of learning engagement in ways less well explored.

Teacher-student relationship and learning engagement

According to the positive youth development theory, teacher-student relationship are not only seen as a fundamental element of the educational process but also as a key developmental resource for promoting students’ academic and personal growth (Lerner et al., 2005). Good teacher-student relationship act as protective factors ensuring adolescents’ healthy growth and development, such as adaptation to school nand partner interaction (Endedijk et al., 2021). Research has found if some students have positive teacher-student relationship, they not only obtain the necessary emotional support and academic guidance, but also learning environments that enable learning engagement (Roorda et al., 2017). More precisely, positive interactions and trust within teachers and their students can increase students’ involvement in classroom activities, interest in learning, and autonomous learning ability (Zee & Roorda, 2018). Furthermore, good teacher-student relationship have the counteracting effect as negative life events and act as a substitute for the lack of negative parent-child relationship, and it can provide the student with a warm and safe environment for learning and growing (McGrath & Van Bergen, 2015). Conversely, negative teacher-student relationship can cause students to lack a sense of security and hinder their learning behavior (Xerri et al., 2018).

Intentional self-regulation as a mediator

Intentional self-regulation is a crucial component of self-regulation and encompasses a series of processes in which individuals actively coordinate environmental resources, demands, and personal behaviors to achieve their chosen goals (Gestsdóttir et al., 2015). Research indicates that intentional self-regulation plays a single of the crucial proximal elements driving the development of individual positive behaviors (Stefánsson et al., 2018). Studies have found that intentional self-regulation, as an important personal developmental advantage, can significantly promote students’ learning engagement and reduce the likelihood of learning frustration (Suan, 2023). Additionally, students with high intentional self-regulation abilities more frequently employ “selection-optimization-compensation” strategies, gaining more successful experiences in the learning process, and thereby feeling a stronger sense of subjective well-being, which further promotes their learning engagement (Wang et al., 2021). Therefore, when students face academic challenges, a good teacher-student relationship could potentially facilitate the enhancement of students’ intentional self-regulation abilities, thereby helping them engage more effectively in learning and optimize learning strategies.

Peer relationship as a moderator

Peer relationship has a profound influence on students’ growth and attitudes toward learning (Wentzel et al., 2017). Researchers have shown that high-quality peer relationship might significantly promote students’ intentional self-regulation, with the teacher-student relationship also playing a critical role (Hernández et al., 2021). Specifically, when the quality of peer relationship is low, good teacher-student relationship may have a stronger positively predictive influence on teenagers’ intentional self-regulation (Chang, 2016) and educational outcomes (Wu et al., 2022). Furthermore, research has found substantial variation in the degree of intentional self-regulation among senior secondary school students with different levels of peer relationship: students with high-quality peer relationship perform better in intentional self-regulation than those with low levels of peer relationship (Skibbe et al., 2012; Montroy et al., 2016). Thus, a high-level peer relationship can significantly improve learning engagement (Shao & Kang, 2022), in that adolescents with high-quality peer relationship experience higher levels of learning engagement (Stefánsson et al., 2018), perhaps with intentional self-regulation.

The positive youth development (PYD) theory highlights how supportive relationships and self-regulation promote adolescents’ academic success and personal growth (Lerner et al., 2005). Teacher-student relationship acts as a critical external resources, fostering intentional self-regulation and learning engagement (Li, 2022). Peer relationship moderates this dynamic, amplifying or buffering the effects of teacher-student relationship on intentional self-regulation and learning engagement, with stronger teacher-student relationship compensating for weaker peer relationship (Wentzel et al., 2017). Grounded in PYD theory, this study extends the framework by examining the mediating role of intentional self-regulation and the moderating role of peer relationship in the context of senior secondary education, providing insights into how social and personal factors interact to enhance learning engagement.

This study aimed to examine the mediating role of intentional self-regulation and the moderating role of peer relationship in the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement. Our research hypotheses were:

H1: Teacher-student relationship predicts higher learning engagement among senior secondary school students.

H2: Intentional self-regulation plays a mediating role in the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement among senior secondary school students to be higher.

H3: Peer relationship moderates the connection between teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation among senior secondary school students to be higher.

H4: Peer relationship moderates the link between intentional self-regulation and learning engagement among senior secondary students to be higher.

H5: Peer relationship moderates the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement among senior secondary school students to be higher.

A total of 540 adolescents from four high schools across Henan Province in central China, were participants. They comprised 261 girls (48.33%) and 279 boys (51.67%). The average age of the participants was 16.56 ± 0.90, with a range of ages from 15 to 18. By school grade, 181 students were from grade 10th (33.52%), 184 students from grade 11th (34.07%), and 175 students from grade 12th (32.41%). Among the participants, 283 were from urban areas (52.41%) and 257 from rural areas (47.59%).

Teacher-student relationship. The Teacher-Student Relationship Scale (TSRS: Zhang, 2003) comprises 22 items to measure four relationship dimensions: conflict, attachment, closeness, and avoidance. The “conflict” dimension contains 9 items, the “attachment” dimension has 5 items, the “closeness” dimension consists of 4 items, and the “avoidance” dimension has 4 items. The items are on a 5-point Likert scale, from “1 = strongly disagree” to “5 = strongly agree”. Higher average scores across all items represent a higher level of teacher-student relationship status. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for TRSR scores 0.931.

Intentional self-regulation. This study employed the Chinese version of the Selection, Optimization, and Compensation Scale (SOCS) adapted by Huang (2021) from intentional self-regulation (SOCS: Gestsdóttir & Lerner, 2007). The SOCS includes three dimensions: selection (6 items), optimization (5 items), and compensation (6 items). The 17 items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree, to 5 = strongly agree. Higher average scores across all items represent a higher level of intentional self-regulation. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the SOCS was 0.935.

Peer relationship. The Peer Relationship Scale for Children and Adolescents (PRSCA: Guo, 2003) comprises dimensions of friendship, peer rejection, and peer acceptance. The PRSCA includes 22 items, with responses measured on a 4-point Likert scale spanning from 1 = strongly disagree, to 4 = strongly agree. Items 11, 12, 15, 17, 19, 20, and 21 necessitate inverse scoring, whereas the remaining items are scored positively. Higher scores indicate poorer peer relationship. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the PRSCA was 0.922.

Learning engagement. The Learning Engagement Scale (LES: Schaufeli et al., 2002), translated by Fang et al. (2008), consists of 17 items scored on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never, to 7 = always. The LES comprises six items for vigor, five items for dedication, and six items for absorption. Higher average scores indicate greater learning engagement. In the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for scores from the LES was 0.942.

The present study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Guangxi Normal University. Participants consented to the study with assurances about anonymity and voluntariness as well as strict confidentiality.

SPSS 25.0 was used to analyze all the data. First, to overcome the potentially harmful effects of common method variance on the conclusions, procedural precautions were taken in the study design by emphasizing anonymity, confidentiality, and balancing item order during the data collection process (Tehseen et al., 2017). Additionally, utilizing Harman’s single-factor test for statistical processing, it was discovered that the first factor only accounted for 26.293% (less than 50%) of the variance in the eigenvalues of the 13 factors greater than 1, indicating that there was no significant common method bias in this study (Schwarz et al., 2017). Then, the researchers carried out an analysis of descriptive statistics, including tests for skewness and kurtosis, as well as a correlation analysis. To test for direct and indirect effects, the study employed the bootstrap confidence interval (CI) method with 5000 bootstrap samples. If the 95% CI does not contain zero, the result is deemed to be statistically significant. Before formal analysis, all variables were standardized (Kim, 2019) to avoid multicollinearity.

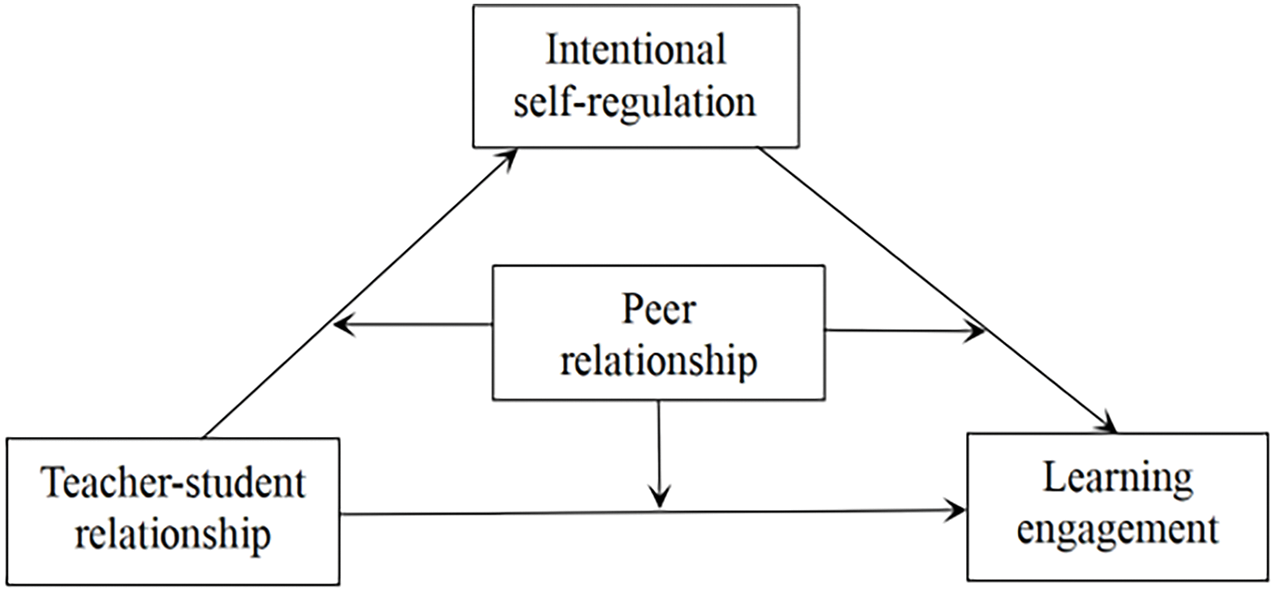

The study examined the mediating effect of intentional self-regulation on the connection between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement by using Model 4 of the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018) for the analysis. In addition, this study conducted a moderated mediation analysis using Model 59 of the SPSS PROCESS macro (Hayes, 2018). We utilized used 5000 bootstrap samples for the bias-corrected percentile Bootstrap technique to assess the model illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Proposed moderated mediation model

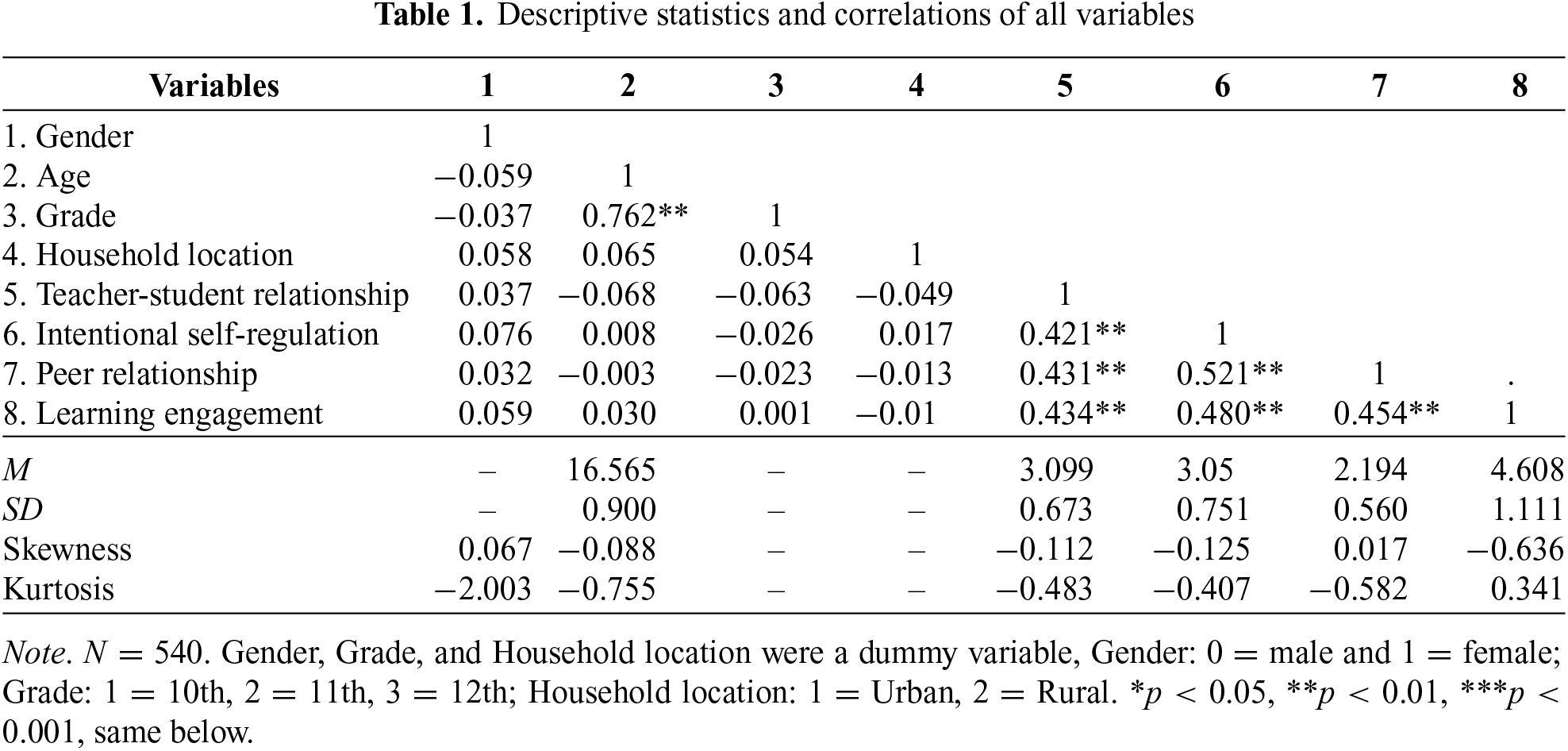

Descriptive statistics and correlational analyses

Table 1 provides the Pearson correlation coefficients, means (M), and standard deviations (SD) for the primary variables. The study revealed strong positive associations between learning engagement and the quality of teacher-student relationship, intentional self-regulation, and peer relationship among senior secondary school students. Moreover, significant positive correlations were shown between intentional self-regulation and peer relationship; teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation, as same as peer relationship. In particular, the results showed no significant correlations between demographic factors (gender, age, grade, and household location) and the study variables, so these variables were not considered further in the analysis of mediation and moderation effects.

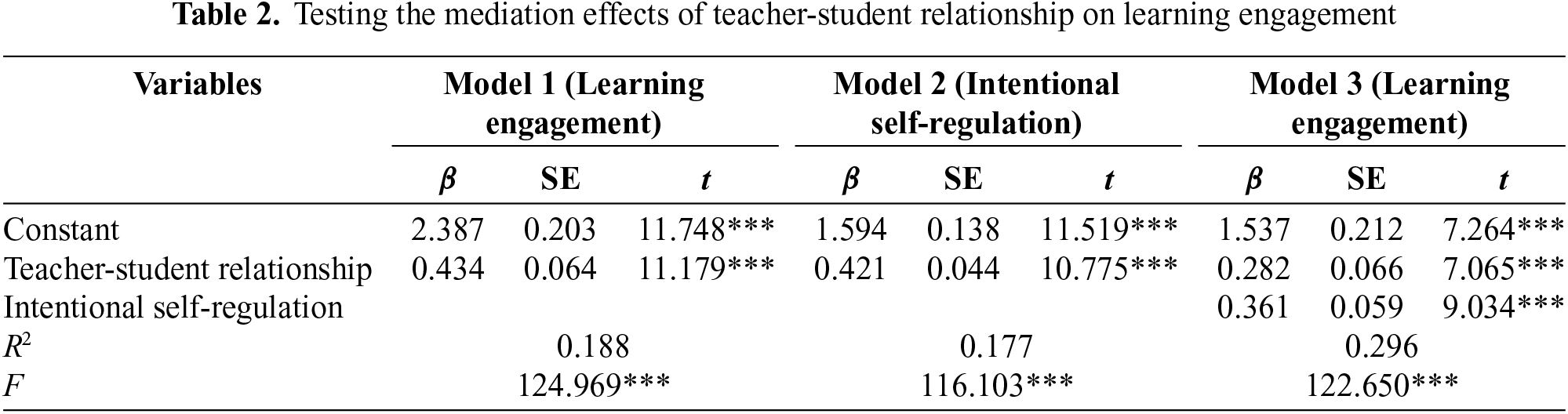

Intentional self-regulation mediation

These mediation analysis findings (see Table 2) indicated that teacher-student relationship significantly positively predicted learning engagement (β = 0.434, t = 11.179, p < 0.001). This result supports Hypothesis 1, demonstrating that a higher teacher-student relationship predicted higher levels of learning engagement.

After including intentional self-regulation as a mediator, the direct impact of the teacher-student relationship on learning engagement was still significant (β = 0.282, t = 7.065, p < 0.001). Teacher-student relationship significantly predicted intentional self-regulation (β = 0.421, t = 10.775, p < 0.001), while intentional self-regulation significantly predicted learning engagement (β = 0.361, t = 9.034, p < 0.001). A percentile Bootstrap technique, including bias correction, further indicated that intentional self-regulation partially mediated the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement, with an indirect effect of 0.152 (Boot SE = 0.023) and a 95% confidence interval of [0.108, 0.198]. Therefore, the mediating role was significant, indicating a partial mediation. The overall effect was 0.434, with the mediating role contributing to 35.02% of the overall effect. The variance in learning engagement among students in senior secondary school was explained by this model to the extent of 29.60%. These results support Hypothesis 2, indicating that intentional self-regulation mediated the relationship between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement to be higher.

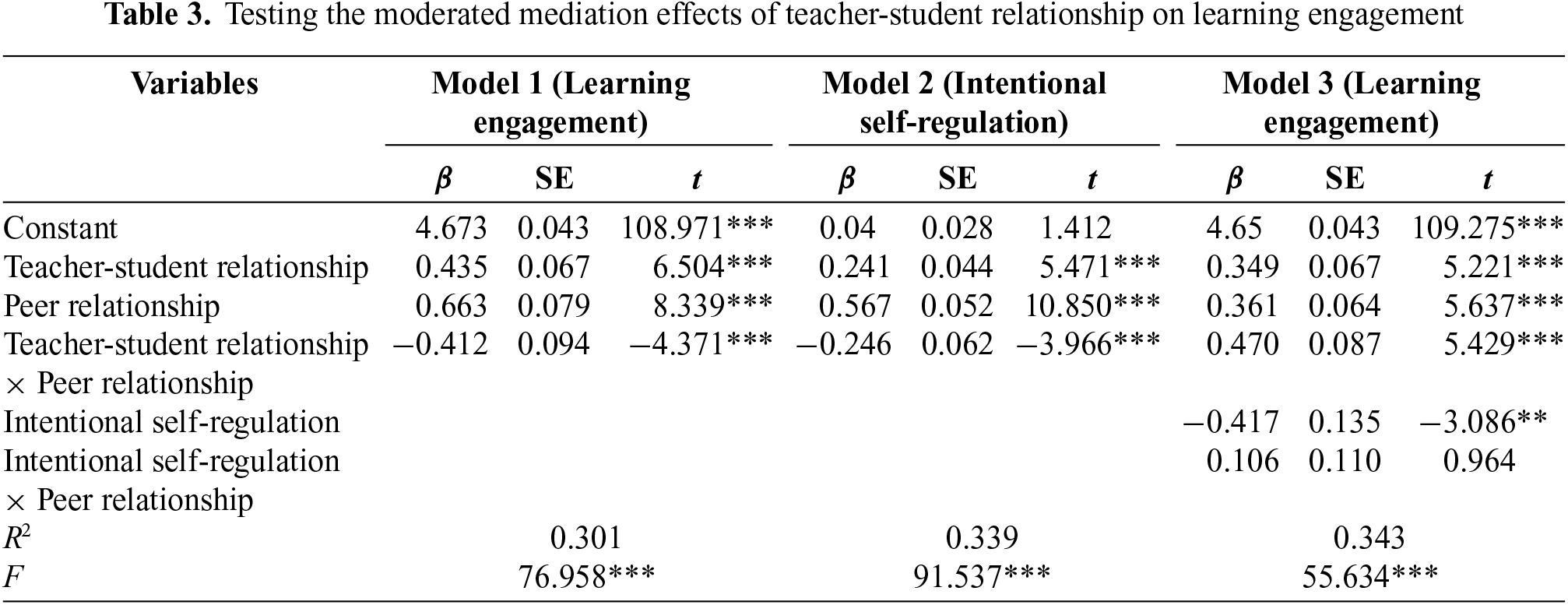

Moderated mediation effect of peer relationship

As shown in Table 3, the interaction between teacher-student relationship and peer relationship significantly predicted learning engagement (β = −0.412, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.025), with a 95% confidence interval of [−0.597, −0.277] (Model 1), showing that peer relationship moderated the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement. Both teacher-student relationship and peer relationship positively predicted intentional self-regulation, and the interaction between teacher-student relationship and peer relationship significantly predicted intentional self-regulation (β = −0.246, p < 0.001, ΔR2 = 0.019), within a 95% confidence interval of [−0.368, −0.124] (Model 2). Moreover, not only teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation positively predicted learning engagement, but also the interaction between teacher-student relationship and peer relationship negatively predicted learning engagement (β = −0.417, p = 0.002, ΔR2 = 0.012), within a 95% confidence interval of [−0.682, −0.151], suggesting that peer relationship moderated the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement. However, the interaction between intentional self-regulation and peer relationship might not significantly predict learning engagement (β = 0.106, p = 0.335, ΔR2 = 0.001), within a 95% confidence interval of [−0.110, 0.323] (Model 3), demonstrating that peer relationship might not moderate the connection between intentional self-regulation and learning engagement. Therefore, peer relationship had a role in moderating both the direct influence of the teacher-student relationship on learning engagement and the first part path of the mediation model, supporting Hypotheses 3 (peer relationship moderates the connection between teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation to be higher) and Hypotheses 5 (peer relationship moderates the relation between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement to be higher).

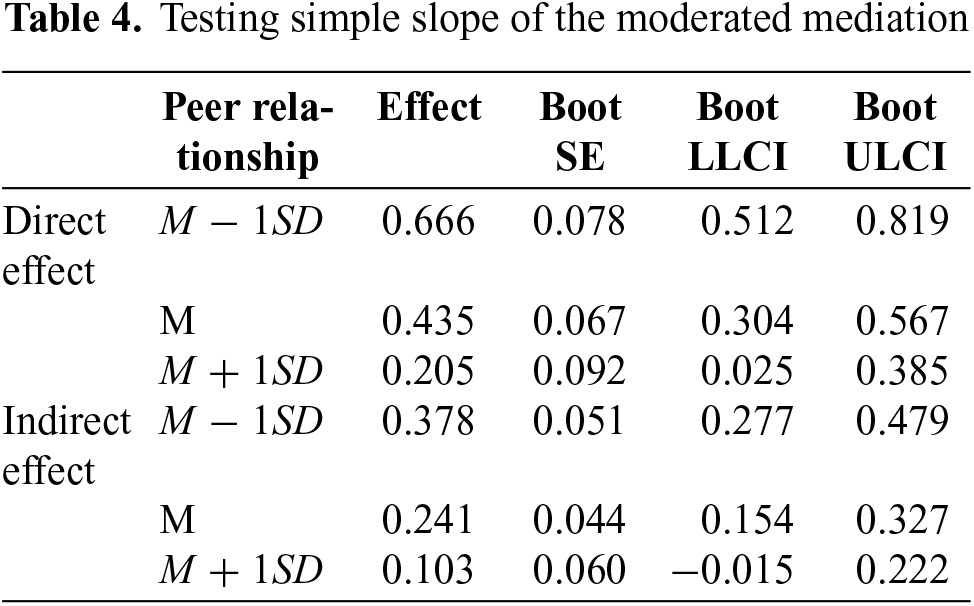

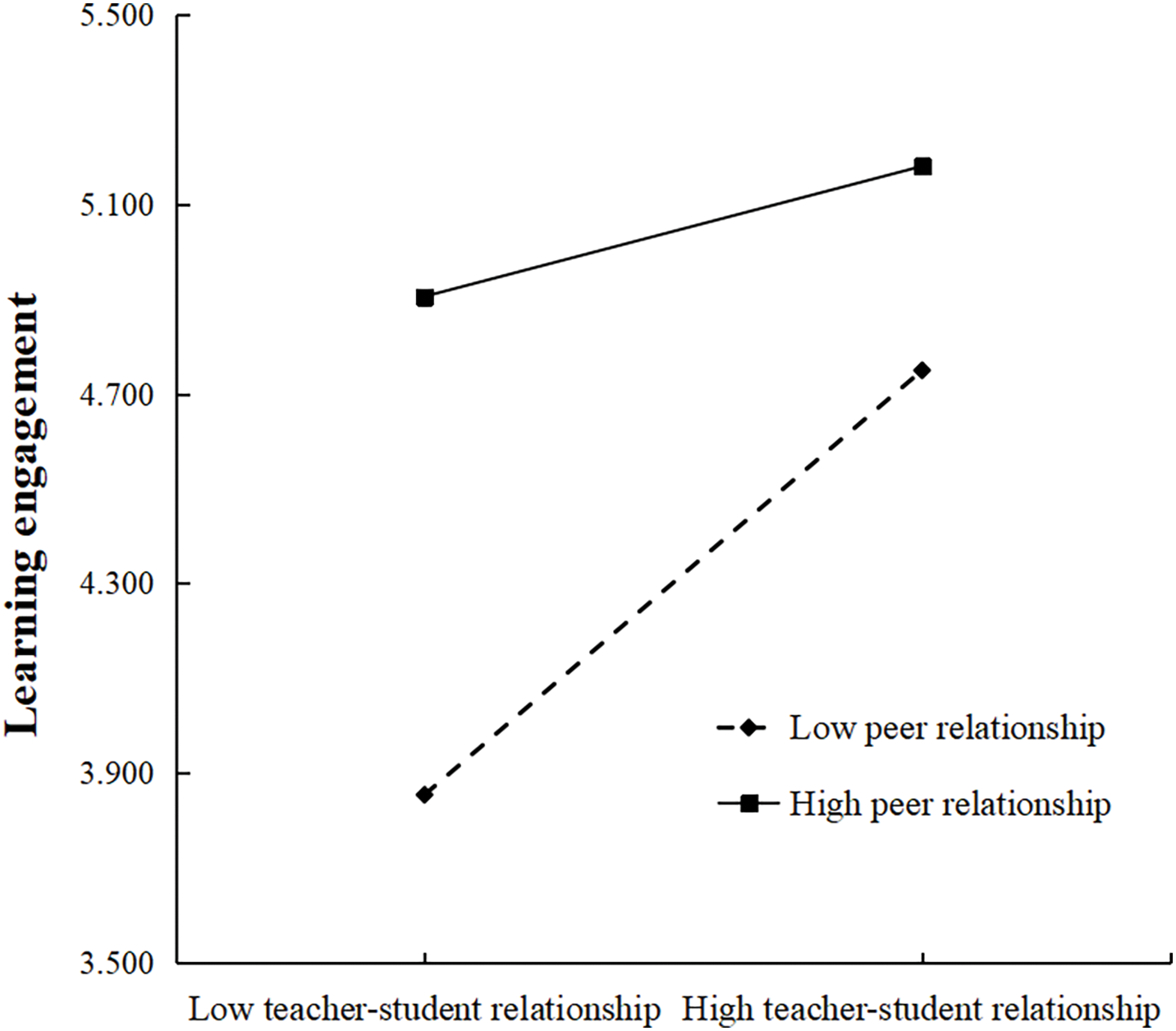

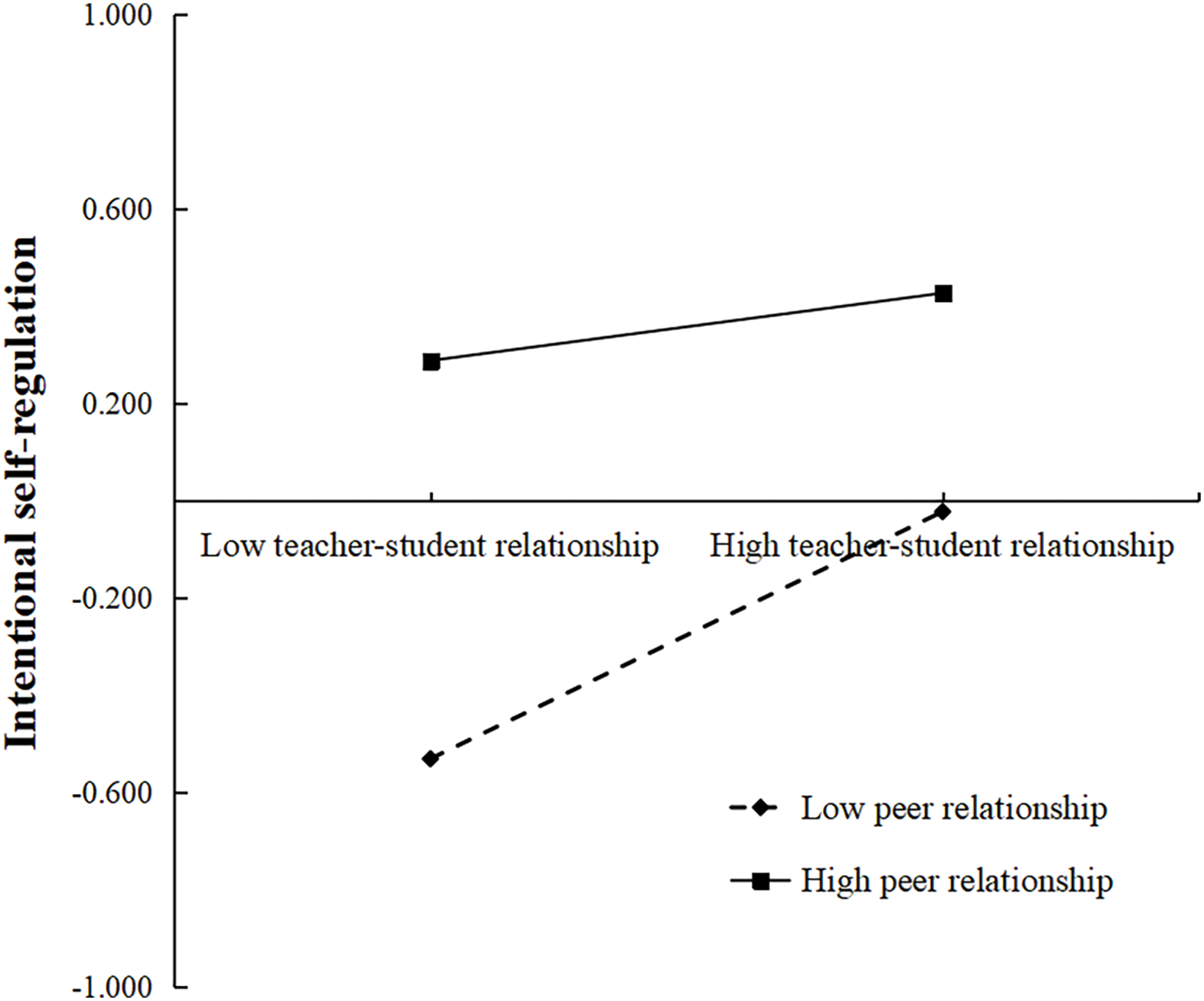

To elucidate the nature of the interaction effects, the high score group is defined as those with peer relationship scores above the mean plus one standard deviation (M + 1SD), and the low score group as those below the mean minus one standard deviation (M − 1SD) (Dawson, 2014). Not only the direct impact of teacher-student relationship on learning engagement but also the indirect impact of intentional self-regulation, along with their 95% Bootstrap confidence intervals, are shown in Table 4. Further, simple slope tests were conducted, with specific moderation effect results shown in Figures 2 and 3. Figure 2 indicates that when peer relationship were poor, teacher-student relationship can significantly positively predict learning engagement (βsimple = 0.666, t = 8.519, p < 0.001), but this impact was attenuated when peer relationship were good (βsimple = 0.205, t = 2.232, p = 0.026). Figure 3 shows that when peer relationship were poor, teacher-student relationship significantly positively predicted intentional self-regulation (βsimple = 0.378, t = 7.361, p < 0.001), but this effect was attenuated when peer relationship were good (βsimple = 0.103, t = 1.712, p = 0.087).

Figure 2. Interaction between teacher-student relationship and peer relationship on learning engagement

Figure 3. Interaction between teacher-student relationship and peer relationship on intentional self-regulation

In summary, the present study discovered that peer relationship moderated the relation between teacher-student relationship, intentional self-regulation, and learning engagement to varying degrees, affecting both the direct link from teacher-student relationship to learning engagement and the first half path of the mediation process.

The teacher-student relationship significantly positively predicted learning engagement. This finding is in line with the positive youth development theory (Lerner et al., 2005), specifically that a good teacher-student relationship provides emotional support, identification, respect, and expectations, which are key elements in promoting a positive attitude and behavior toward learning among senior secondary school students (Thornberg et al., 2022). Thus, good teacher-student relationship might serve as a beneficial factor for learning engagement among senior secondary school students. Previous studies have also found that harmonious teacher-student relationship can also enhance students’ sense of security, create a warm learning atmosphere for students, and lay a good foundation for learning engagement (Zee & Roorda, 2018).

Intentional self-regulation partially mediated the relationship between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement to be higher, and likely by fostering students’ positive developmental outlook and promoting harmony between the individual and both the environment and the self. Specifically, a democratic and supportive teacher-student relationship provides students with respect, care, and encouragement, creating an external environment that supports the development of intentional self-regulation (Stefánsson et al., 2018). Meanwhile, intentional self-regulation aligns individuals’ cognition, behavior, and emotion, allowing adolescents to continuously adjust strategies and achieve goal-oriented behaviors during the period of rapid self-awareness development, thus enhancing learning engagement (Portilla et al., 2014). Hence, intentional self-regulation plays a very important role in individual positive development (Gestsdóttir et al., 2017).

Peer relationship significantly moderated the relation between teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation among senior secondary school students, highlighting its association with cognitive, emotional, and behavioral self-regulation (Raufelder et al., 2015). This finding underscored the key role of teachers in supporting adolescents’ involvement with peers. When peer support is insufficient, teacher-student relationship play a compensatory role, providing emotional support and behavioral guidance to promote self-regulation (Farley & Kim-Spoon, 2014). To foster positive adolescent development, schools should not only strengthen teacher-student relationship but also implement targeted interventions to cultivate healthy peer interactions and enhance students’ self-regulation.

Peer relationship significantly moderated the teacher-student relationship and learning engagement among senior secondary school students to be higher. For adolescents with weaker peer relationship, attention and support from teachers become key to their successful learning experiences, acting as a compensatory mechanism to enhance their learning engagement (Engels et al., 2016; Grew et al., 2022). This highlights the critical role of teacher-student relationship in fostering emotional and motivational resources, particularly when peer support is insufficient, thereby promoting academic outcomes (Furrer et al., 2014; Hoferichter et al., 2022).

Implications for student development

This study offers a new perspective on enhancing students’ learning engagement, applying positive youth development theory (Lerner et al., 2005) and developmental systems theory (Griffiths & Hochman, 2015). For instance, according to youth development theory, understanding how and when intentional self-regulation and peer relationship impact teacher-student relationship for learning engagement would enrich school environmental factors for student quality of school life. Similarly, developmental systems theory posits that student development services should regard intentional self-regulation as a crucial resource for leveraging teacher-student relationship for learning engagement. Specifically, schools should promote students’ self-regulation abilities by establishing a supportive and encouraging learning environment and valuing the cultivation of positive personal qualities, which may help enhance learning engagement (Opdenakker, 2022). Second, teachers should actively build positive relationships with students by providing support through regular one-on-one meetings, positive feedback, and continuous attention to students’ learning progress. Encouraging students to participate in beneficial social activities would promote excellent peer relationships with closer connections with positive peers.

Limitations and future directions

Despite valuable findings, the current study has limitations that warrant acknowledgement. First, the cross-sectional study design of the present study cannot determine causal relationships between variables nor their long-term effects. Future research might consider longitudinal designs to explain the causality of these relationships. Second, the student sample was drawn from only four high schools, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research should include a more diverse and representative sample to further validate the relationships. Third, the data is derived solely from participants’ self-reports, which may introduce errors (e.g., social desirability, and memory biases). Future research might look into collecting data from a variety of sources (peers, teachers, parents) to measure related variables more objectively. Finally, this study investigated specifically the the teacher-student relationship and learning engagement, focusing on intentional self-regulation and peer relationship among senior secondary school students. Subsequent studies might further examine the effects of other different mediating and moderating factors.

To sum up, the present study aids our understanding of the potential mechanisms linking teacher-student relationship and learning engagement. Teacher-student relationship predicts learning engagement outcomes among senior secondary school students. Mediation analysis shows that intentional self-regulation may be an explanatory factor in how positive teacher-student relationship improve learning engagement among senior secondary school students. Additionally, the moderated mediation analysis indicates that peer relationship might moderate the relation between teacher-student relationship and intentional self-regulation, as well as the relationship between teacher-student relationship and learning engagement among senior secondary school students. Therefore, enhancing learning engagement requires fostering intentional self-regulation and supportive teacher-student relationship. By addressing students’ academic and emotional needs and improving peer relationship, schools can create an environment that promotes goal-directed behaviors and positive youth development, ultimately boosting learning engagement.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to all the students, parents, and teachers who participated or contributed to this project.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Mengjun Zhu: conceptualize the aims and hypotheses, database creation, and manuscript writing and revising. Xing’an Yao: data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, and manuscript writing. Xing’an Yao is listed as co-first author and corresponding author. Mansor Bin Abu Talib: conceptualization, writing—review and editing, supervision. Mansor Bin Abu Talib is listed as corresponding author. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: This study was approved by the Academic Committee of Guangxi Normal University, in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Chang, H. (2016). The perceptions of temporal path analysis of learners’ self-regulation on learning stress and social relationships in junior high school. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2016.040105 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dawson, J. F. (2014). Moderation in management research: What, why, when, and how. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-013-9308-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., Van Lissa, C. J., Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Boer, L. D., et al. (2021). The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher-student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Review of Educational Research, 92(3), 370–412. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543211051428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Engels, M. C., Colpin, H., Van Leeuwen, K., Bijttebier, P., Van Den Noortgate, W., et al. (2016). Behavioral engagement, peer status, and teacher-student relationships in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal influences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(6), 1192–1207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0414-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fang, L. T., Shi, K., & Zhang, F. H. (2008). Research on reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale-Student. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(6), 618–620. https://doi:CNKI:SUN:ZLCY.0.2008-06-022 [Google Scholar]

Farley, J. P., & Kim-Spoon, J. (2014). The development of adolescent self-regulation: Reviewing the role of parent, peer, friend, and romantic relationships. Journal of Adolescence, 37(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Furrer, C., Skinner, E. A., & Pitzer, J. R. (2014). The influence of teacher and peer relationships on students’ classroom engagement and everyday motivational resilience. Teachers College Record, 116(13), 101–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146811411601319 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gestsdóttir S., Geldhof G. J., Paus T, Freund A. M., Adalbjarnardottir S., et al. (2015). Self-regulation among youth in four Western cultures. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(4), 346–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414542712 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gestsdóttir, S., Geldhof, G. J., Lerner, J. V., & Lerner, R. M. (2017). What drives positive youth development? Assessing intentional self-regulation as a central adolescent asset. International Journal of Developmental Science, 11(3–4), 69–79. https://doi.org/10.3233/dev-160207 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gestsdóttir, S., & Lerner, R. M. (2007). Intentional self-regulation and positive youth development in early adolescence: Findings from the 4-h study of positive youth development. Developmental Psychology, 43(2), 508–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/00 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grew, E., Baysu, G., & Turner, R. N. (2022). Experiences of peer victimization and teacher support in secondary school predict university enrolment 5 years later: Role of school engagement. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 1295–1314. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Griffiths, P. E., & Hochman, A. (2015). Developmental systems theory. In Encyclopedia of Life Sciences (pp. 1–7). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470015902.a0003452 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Guo, B. L. (2003). The impact of classroom climate on rural children’s social behavior and its relationship to school adjustment [Doctoral dissertation]. China: The Chinese University of Hong Kong. [Google Scholar]

Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Hernández M. M., Valiente C., Eisenberg N., Spinrad T. L., et al. (2021). Do peer and child temperament jointly predict student-teacher conflict and closeness? Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 76, 101319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101319 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hoferichter, F., Kulakow, S., & Raufelder, D. (2022). How teacher and classmate support relate to students’ stress and academic achievement. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 992497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.992497. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Huang, Y. (2021). The relationship between mother-adolescent conflicts and depression of junior senior secondary school students: The role of intentional self-regulation [Doctoral dissertation]. China: East China Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Kim, J. H. (2019). Multicollinearity and misleading statistical results. Korean Journal of Anesthesiology, 72(6), 558–569. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.19087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lerner, R. M., Almerigi, J. B., Theokas, C., & Lerner, J. V. (2005). Positive youth development a view of the issues. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 25(1), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431604273211 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, J. (2022). Teacher-student relationships and academic adaptation in college freshmen: Disentangling the between-person and within-person effects. Journal of Adolescence, 94(4), 538–553. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12045. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

McGrath, K., & Van Bergen, P. (2015). Who, when, why and to what end? Students at risk of negative student-teacher relationships and their outcomes. Educational Research Review, 14, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2014.12.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Montroy, J. J., Bowles, R. P., & Skibbe, L. E. (2016). The effect of peers’ self-regulation on preschooler’s self-regulation and literacy growth. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 46, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2016.09.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Opdenakker, M. (2022). Developments in early adolescents’ self-regulation: The importance of teachers’ supportive vs. undermining behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 497. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1021904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Portilla, X. A., Ballard, P. J., Adler, N. E., Boyce, W. T., & Obradović, J. (2014). An integrative view of school functioning: Transactions between self-regulation, school engagement, and teacher-child relationship quality. Child Development, 85(5), 1915–1931. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Rahman M. A., Todd C., John A., Tan J., Kerr M., et al. (2018). School achievement as a predictor of depression and self-harm in adolescence: Linked education and health record study. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 212(4), 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2017.69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Raufelder, D., Hoferichter, F., Schneeweiss, D., & Wood, M. A. (2015). The power of social and motivational relationships for test-anxious adolescents’ academic self-regulation. Psychology in the Schools, 52(5), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21836 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sang, B., Pan, T., Deng, X., & Zhao, X. (2018). Be cool with academic stress: The association between emotional states and regulatory strategies among Chinese adolescents. Educational Psychology, 38(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1309008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schwarz, A., Rizzuto, T., Carraher-Wolverton, C., Roldán, J. L., & Barrera-Barrera, R. (2017). Examining the impact and detection of the “Urban legend” of common method bias. ACM SIGMIS Database: the DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 48(1), 93–119. https://doi.org/10.1145/30514733051479 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shao, Y., & Kang, S. (2022). The association between peer relationship and learning engagement among adolescents: The chain mediating roles of self-efficacy and academic resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 938756. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.938756. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Skibbe, L. E., Phillips, B. M., Day, S. L., Brophy-Herb, H. E., & Connor, C. M. (2012). Children’s early literacy growth in relation to classmates’ self-regulation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 104(3), 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029153 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stefánsson, K. K., Gestsdóttir, S., Birgisdóttir, F., & Lerner, R. M. (2018). School engagement and intentional self-regulation: A reciprocal relation in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 64(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.01.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Suan, A. F. (2023). Self-regulation as an antecedent of academic achievement: A mixed method study. British Journal of Multidisciplinary and Advanced Studies, 4(4), 20–43. https://doi.org/10.37745/bjmas.2022.0246 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. https://doi.org/10.20547/jms.2014.1704202 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thornberg, R., Forsberg, C., Hammar Chiriac, E., & Bjereld, Y. (2022). Teacher-student relationship quality and student engagement: A sequential explanatory mixed-methods study. Research Papers in Education, 37(6), 840–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1864772 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, H., Yang, J., & Li, P. (2021). How and when goal-oriented self-regulation improves college students’ well-being: A weekly diary study. Current Psychology, 41(1), 17532–7543. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01288-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wentzel, K. R., Muenks, K., McNeish, D., & Russell, S. L. (2017). Peer and teacher supports in relation to motivation and effort: A multi-level study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.11.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, F., Jiang, Y., Liu, D., Konorova, E., & Yang, X. (2022). The role of perceived teacher and peer relationships in adolescent students’ academic motivation and educational outcomes. Educational Psychology, 42(4), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2022.2042488 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xerri, M. J., Radford, K., & Shacklock, K. (2018). Student engagement in academic activities: A social support perspective. Higher Education, 75(4), 589–605. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0162-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zee, M., & Roorda, D. L. (2018). Student-teacher relationships in elementary school: The unique role of shyness, anxiety, and emotional problems. Learning and Individual Differences, 67, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2018.08.006 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, L. (2003). A study on the characteristics of teacher-student relationship among secondary school students and its relationship with school adaptation [Doctoral dissertation]. China: Beijing Normal University. [Google Scholar]

Zhen, R., Liu, R., Ding, Y., Liu, Y., Wang, J., & Xu, L. (2018). The moderating role of intrinsic value in the relation between psychological needs support and academic engagement in mathematics among Chinese adolescent students. International Journal of Psychology, 53(4), 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12374. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools