Open Access

Open Access

The serial mediating role of future self-awe and depression: The serial mediating role of future self-continuity and the presence of meaning

Student Affairs Department, Civil Aviation University of China, Tianjin, 300300, China

* Corresponding Author: Yujing Tao. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 99-105. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065783

Received 08 July 2024; Accepted 26 October 2024; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

This study investigated the relationship between college students’ awe and depression, along with the mediating roles of future self-continuity and presence of meaning. 891 Chinese college students (570 female; mean age 18.59; SD 1.34) from one university completed four surveys: Dispositional Awe Subscale, Future self-continuity Scale, Meaning in Life Scale and Depression Scale. Using structural equation modelling and the bootstrap method, the results delineated that awe negatively related to depression, and future self-continuity and presence of meaning had a serial mediation effect, reducing depression. The study implies educational institutions should foster a positive mental health education environment, urging students to develop positive traits, enhancing well-being and resilience, and facilitating psychological development.Keywords

Depression refers to an emotional problem characterized by low mood, feelings of hopelessness, lack of energy, or easy fatigue (Herrman et al., 2022). As a predominant concern within global mental health discourse, depression has garnered considerable attention from researchers worldwide. The youth period, especially among college students, is a critical time for the onset of common mental disorders (Jiang & Zhang, 2023). The incidence of depression within this cohort, evidenced by existing literature, is notably higher compared to other segments of the population (Goodwin et al., 2022). Depression not only significantly impacts psychological and social functioning, such as academic performance, subjective well-being, and interpersonal relationships, but can also lead to severe outcomes such as suicide (Monzonís-Carda et al., 2021; Li et al., 2023). According to estimates, 23.8% of Chinese university students have screened positive for depression (Chen et al., 2022); currently, numerous Chinese college students are suffering from “hollow heart syndrome”, which reflects their immaturity, lack of self-exploration and contemplation of meaning in life (Paulos & Kaiwen, 2019). College students are in the important youth period in their life, and their mental health plays an important role in having harmonious interpersonal relationship, cultivating independent and sound personality, and establishing future life goals. Previous researches on depression among college students have mainly focused on the prevalence of such disorders, influencing factors, and potential negative impacts. Yet, there is limited research on positive factors that can buffer against depression among college students. In recent years, with the rise of positive psychology, awe has gradually entered the field of psychology as a positive emotion. Chirico and Gaggioli (2021) have demonstrated that experiences of awe can ameliorate depressive symptoms, interest in the unique pathways linking awe to mental health outcomes has gained increasing attention, awe can diminish focus on the self, increase prosocial relationality, facilitate greater social integration, and generate a heightened sense of meaning—that benefit well-being (Bai et al., 2021; Monroy & Keltner, 2023), it is critical to healthy adaption on life (Chen & Mongrain, 2021), but the role of awe is yet to be elucidated, the necessity for further exploration into the mechanisms underpinning this relationship is apparent.

Awe and correlates of depression

Awe arises from encountering stimulus that transcend personal or preconceived cognitive dimensions, eliciting a profound sense of vastness that demands new mental constructs for comprehension such as conformity. When people encounter magnificent and sublime things, they experience awe (Keltner & Haidt, 2003; Monroy & Keltner, 2023; Weger & Wagemann, 2021). Awe is a positive emotion that may protect against negative events due to its ability to elicit the “small self” and prevent depression symptoms (Schaffer et al., 2024). Previous studies have found that there is a positive correlation between awe and future self-continuity (Pan & Jiang, 2023), future self-continuity refers to the degree to which individuals perceive a strong connection between their present self and their future self (Ersner-Hershfield et al., 2009). An integral component of awe, a sense of connectedness, can facilitate individuals in linking their present and future selves (Schneider, 2009); while lower levels of future self-continuity are linked to increased risks of adverse mental health outcomes such as depressive symptoms and suicide (Sokol & Serper, 2016). Santo et al. (2018) found that high levels of future self-continuity moderated individuals’ depressive symptoms. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, 1998) suggests that positive emotions cognitive and attentional parameters, thus catalyzing the generation of novel thoughts and ideas. That is, emotions can promote the resolution of various social problems in which humans live by influencing the core mediator of self (Bai et al., 2017). As a result, future self-continuity may mediate the relationship between awe and depression.

Meaning in life refers to individuals’ understanding and pursuit of purpose and goals. Steger et al. (2008) conceptualized meaning in life from two dimensions, where the presence of meaning dimension refers to individuals understanding the meaning of life and being aware of their purpose, goal, or mission. Dai et al. (2022) established that awe invigorates the presence of meaning, while concurrently, the essence of depression is often linked to an absence of life’s meaning (Frankl, 1992), King and Hicks (2021) found that the presence of meaning is an essential indicator of mental health among college students. From a psychodynamic perspective, fulfilling basic psychological needs predisposes individuals towards cultivating positive psychological attributes, engendering a propensity to seek and engage in meaningful life experiences, thereby enriching the perceived value and meaning of their existential experience (Halusic & King, 2013). Conversely, individuals with unmet basic psychological needs are more prone to anxiety, depression, and a higher risk of suicide due to a lack of meaningful life experiences (Bamonti et al., 2016; Heisel & Flett, 2016). Hence, presence of meaning can mediate the relationship between awe and depression.

The mediating effects of future self-continuity and presence of meaning are not parallel. Previous studies have shown that future self-continuity can promote the presence of meaning (Xue et al., 2023), as perceiving a stable sense of self confers a sense of certainty about one’s life (Mai et al., 2023). Cognitive vulnerability model of depressive states that when an individual has a negative perception of himself, he is more likely to adopt a negative attitude to anticipate the future, resulting in depression (Abramson et al., 1978; Beck, 1967; Ingram, 2003), when individuals have positive self-awareness, they can relieve depression through self-affirmation and positive evaluation (Orth et al., 2016).

The researchers found that awe could offer a wide range of psychological benefits via facilitating the temporal integration of self-concept (i.e., future self-continuity). As a key indicator of psychological maturity, future self-continuity has been found positively associated with psychological well-being and adaptive behavior (Conway et al., 2004; Lodi-Smith et al., 2017). Rooted in the mental simulation theory of future self-continuity (Baumeister & Masicampo, 2010) it is posited that individuals with high future self-continuity are adept at mentally transcending temporal confines. They can vividly envision distinct timeframes—both past and impending futures—alongside divergent locales and subjective realms. This expansive mental faculty engenders a more profound presence of meaning. And presence of meaning can minimize depression and to promote the society general health would be helpful (Maryam Hedayati & Mahmoud Khazaei, 2014). Therefore, awe can promote the positive self-cognition of individuals due to its self-transcendence function, thus reducing the possibility of depression. Therefore, we have reason to assume that future self-continuity and presence of meaning have a chain mediation effect between awe and depression.

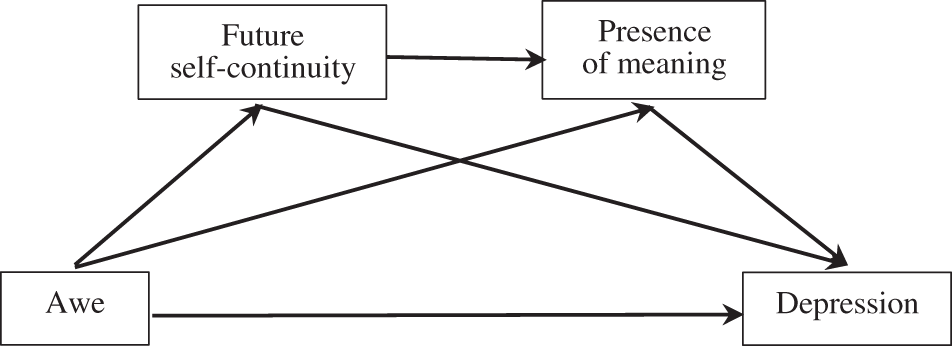

This study aimed to model the awe on depression with mediation by the future self-continuity and presence of meaning. Figure 1 presents our conceptual model. We tested the following hypotheses:

Figure 1. Theoretical model

H1: Awe negatively influences depression.

H2: Future self-continuity mediates the relationship between awe and depression.

H3: Presence of meaning mediates the relationship between awe and depression.

H4: Future self-continuity and presence of meaning will have a serial mediating effect between awe and depression.

Participants were 891 college students from one university in Tianjin Province, China. In the sample, the mean age was 18.59 years (SD age = 1.34, range = 16–26 years). Most participants were male (63.97%) and 321 were female (36.02%).

Due to initially being developed in English, the questionnaires were translated from English into Chinese and then back-translated into English to ensure equivalency of meaning (Brislin, 1970).

Awe was measured with a 6-item Dispositional Awe Subscale, adapted from the Dispositional Positive Emotions Scale developed by Shiota et al. (2006). Sample items include “I feel wonder almost every day”. The scales were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree). This scale is widely used in Chinese subjects and has good reliability and validity (Pan & Jiang, 2023). The Cronbach’s α was 0.88.

Future self-continuity was measured with a 10-item Future self-continuity Scale developed by Sokol and Serper (2020). Sample items include “Similarities between you now and ten years from now”. This scale is widely used and its correlation with awe has been confirmed by some studies (Pan & Jiang, 2023). The scales were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 7 (Exactly). The Cronbach’s α was 0.87.

Presence of Meaning was measured with a 5-item Presence of Meaning Subscale, adapted from the Meaning in Life Scale developed by Steger et al. (2006). Sample items include “I have a good sense of what makes my life meaningful”. The scales have been widely used in adolescents and adults with good reliability and validity. The scales were rated on a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (absolutely untrue) to 7 (absolutely true). The Cronbach’s α was 0.82.

Depression was measured with a 20-item Depression Scale developed by Zung (1965). Sample items include “I feel down-hearted and blue”. The scales were rated on a four-point scale ranging from 1 (A little of the time) to 4 (Most of the time). The scale is widely used in the study of the prevalence of depression and has good reliability and validity (Dunstan et al., 2017). The Cronbach’s α was 0.86.

Experts emphasize the crucial and justified selection of control variables (Bernerth & Aguinis, 2016); we included several control variables: subordinates’ gender (1: male, 2: female), and age (measured in years).

The study obtained approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the Civil Aviation University of China. Written informed consent and assent forms were obtained from the participants. The participants gave informed consent. We assured participants that the study was voluntary, that their data would remain confidential, and it would be used only for academic purposes. Data were collected online in October 2023.

We employed SPSS 22.0 and AMOS 26.0 to execute all analyses. Structural equation modelling (SEM) was employed to examine the path relationship between the four variables. Based on 5000 random repeated samples, we tested the mediating effect of future self-continuity and presence of meaning between awe and depression, applying the 95% confidence interval of the mediating effect using the deviation-corrected nonparametric percentile bootstrap method.

Testing for common method bias

This study only collected data through self-report measures, which may lead to common method bias (CMV) issues. To further enhance the rigor of the study, Harman’s single factor test was conducted to statistically control for this bias before analyzing the data. Specifically, an unrotated principal component factor analysis was performed on all items of the variables. The results showed that the first factor accounted for 25.60% of the variance, which is below the critical threshold of 40% (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Therefore, this study’ data does not suffer from severe common method bias.

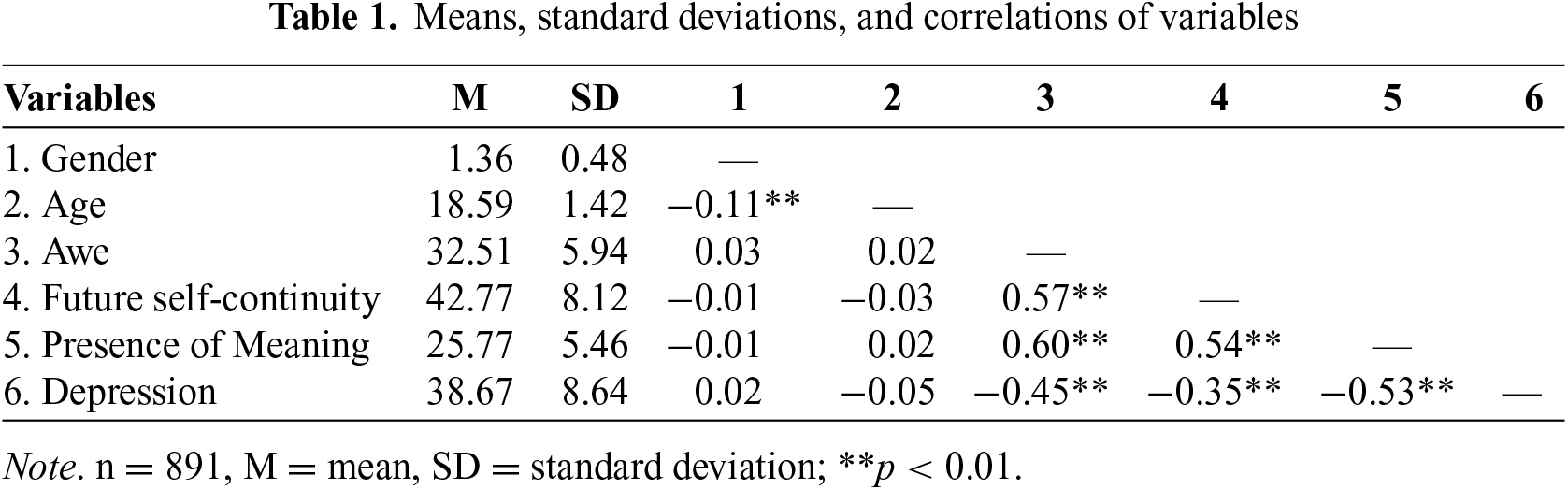

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

The means, standard deviations, and correlations between the research variables are listed in Table 1. As expected, we observed significant relationships between the predictor variables (Awe, Future self-continuity, Presence of Meaning) and the criterion variable (depression). Therefore, hypothesis 1 was also supported. These results set the basis for us to examine the relationship between Awe and depression among subordinates.

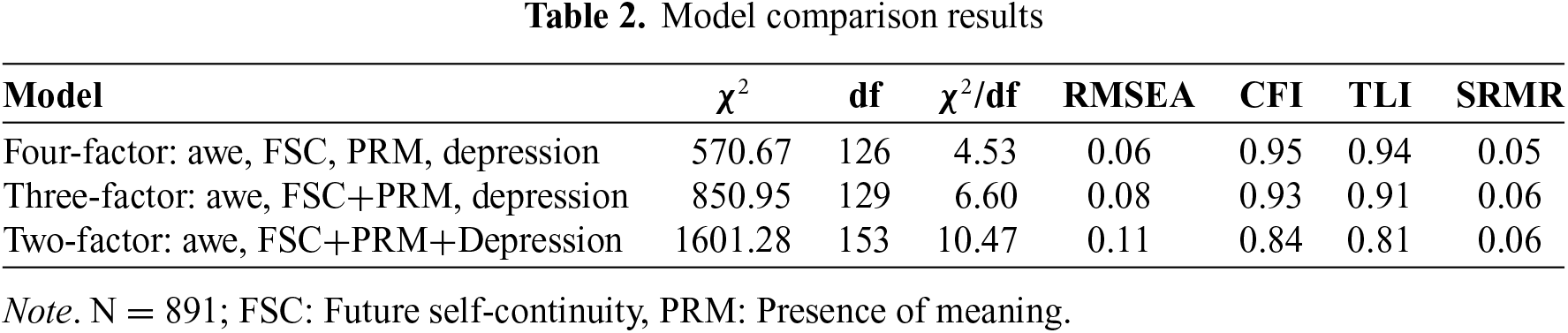

Confirmatory factor analyses were conducted to assess both convergent and discriminant validity. Model fit was assessed using multiple indices, including the χ2 statistic, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), comparative fit index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR). We applied Dyer et al. (2005) approach of multilevel confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) to verify the distinctiveness of factors. Consistent with our anticipations, a four-factor model (awe, FSC, MIL, depression) indicated a reasonably adequate fit (χ2/df = 4.53, RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.94; SRMR = 0.05; see Table 2).

Future self-continuity mediation

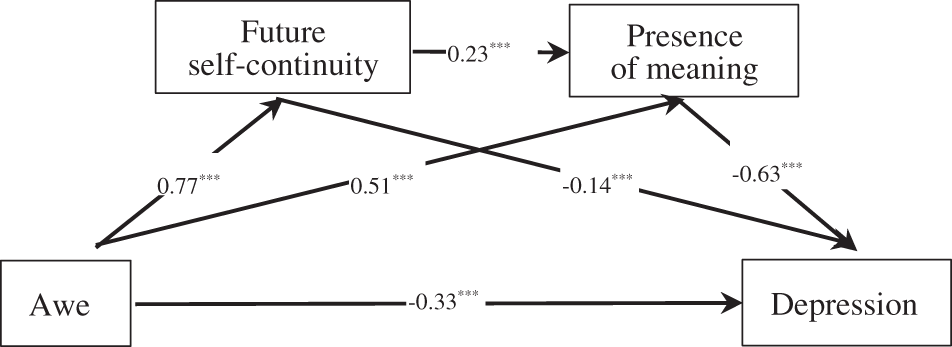

Model 4 of the PROCESS macro was adopted to test Hypothesis 2 and 3, which presumed that future self-continuity would mediate the relation between awe and depression. The results indicated that awe was positively associated with future self-continuity (b = 0.77, p < 0.001), which in turn was related to depression (b = −0.14, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the residual direct effect was significant (b = −0.53, p < 0.001), which means that future self-continuity partly mediated the relation between awe and depression. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Furthermore, presence of meaning would mediate the relation between awe and depression. The results indicated that awe was positively associated with presence of meaning (b = 0.51, p < 0.001), which in turn was related to depression (b = −0.63, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the residual direct effect was significant (b = −0.34, p < 0.001), which means that presence of meaning partly mediated the relation between awe and depression. Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Future self-continuity and presence of meaning serial mediation

Model 6 of the PROCESS macro was adopted to test Hypothesis 4, which presumed that the chain-mediated effect of future self-continuity and presence of meaning. We performed 2000 repetitions of resampling to test the mediation effect and estimate the confidence interval. If the 95% confidence interval does not include 0, it indicates a significant indirect effect. The results showed that there is a chain-mediated effect between future self-continuity and presence of meaning through awe and depression (indirect effect = −0.11, 95%CI: −0.15, −0.08), with an effect size of 36.27%. Therefore, hypothesis 4 is supported.

Figure 2 shows the results of our mode.

Figure 2. Serial mediation model shows the relationship of awe, future self-continuity, presence of meaning, with depression as a covariate (N = 891). There is a chain-mediated effect between future self-continuity and presence of meaning through awe and depression. Values shown are unstandardized coefficients. Note. ***p < 0.001.

The relationship between awe and depression among college students has increasingly captured the scholarly interest of psychological research, yet the specific mechanisms that facilitate this connection remain unexplored. Therefore, based on relevant theoretical and empirical studies, we examined whether future self-continuity and presence of meaning would mediate this relationship among Chinese college students, consistent with previous research (Frankl, 1992; Santo et al., 2018). The findings also corroborated previous research that awe improves individual levels of depression, which may indicate that awe is an important protective factor against depression (Chirico & Gaggioli, 2021). In alignment with the socioemotional selection theory (Carstensen, 1987) and the extended-now theory (Vohs & Schmeichel, 2003), for the high-stress and fast-paced modern society, the experience of awe focuses people’s attention to the present moment, expands their perception of the abundance of time, and enhances the belief in having sufficient time (Luo et al., 2023), expanding an individual’s scope of action and enhancing psychological well-being.

This study also found that awe can positively predict future self-continuity, this finding aligns with previous research, according to the Sundararajan’s expanded model of awe (Sundararajan, 2002), awe promotes self-reflexivity, that when people feel awe, they are able to combine their present and future selves through conformity, allowing them to reflect on their lives and stimulate the pursuit of self-realization (Shiota et al., 2007; Stellar, 2021). College students’ awe can negatively influence depression through future self-continuity, which is consistent with previous research. That is, positive emotions can promote the resolution of various social problems in which humans live by influencing the core mediator of self (Bai et al., 2017). The findings also validate the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions that people judge their lives to be more satisfying and fulfilling, not because they feel more positive emotions, but because their greater positive emotions help them successfully construct life resources (Fredrickson, 1998).

Furthermore, the findings found that awe positively affects the existence of meaning in life, which confirms the feelings-as-information model theory (Schwarz, 2001), in which individuals use their emotions to judge their experiences and attitudes toward the world, and people who feel happy are more likely to perceive their lives as meaningful. This study confirmed the mediating role of presence of meaning between awe and depression. From a psychodynamic perspective, when basic psychological needs are met, individuals are more likely to develop positive psychological qualities, better discover and pursue meaningful experiences in life and better experience the meaning and value of their own lives (Halusic & King, 2013). Conversely, a deficit in such meaningful engagements due to unmet basic needs predisposes individuals to heightened levels of anxiety, depressive states, and an elevated susceptibility to suicidal ideations (Bamonti et al., 2016; Heisel & Flett, 2016).

Finally, this study found serial-mediated effects of future self-continuity and presence of meaning. Future self-continuity promotes presence of meaning as previous research (Xue et al., 2023). Accordingly, a stabilized sense of self engenders life-certainty, empowering individuals to reengage with their deeper selves, ponder existential queries, and recalibrate life aspirations and values. This process fosters a constructive worldview, significantly alleviating the predisposition towards depression. This intricate web of psychological constructs underscores the transformative potential of awe in shaping mental health landscapes, proposing nuanced pathways through which individuals might navigate the tumultuous terrains of depression.

Implications for College Education

The adolescent mental health dilemma has a long history. The emphasis on scores and utilitarianism in elementary education leads to confusion and perplexity among freshmen entering college. When they are confronted with tremendous academic and career pressures, they will experience “hollow disease”, which is prone to depression due to the lack of a sense of meaning and future goals to support them (Terrell et al., 2024). This study provides a new perspective on depression prevention and intervention by focusing on positive factors that buffer depression among college students. The elimination of psychological problems among college students is not only due to a reduction in negative factors but also because of an increase in positive factors and the enhancement of their ability to address their psychological problems. In schools, positive psychological education should be integrated into daily education and teaching, schools should organize outdoor adventure activities and let students experience awe when in contact with nature, at the same time, setting up a course about the awe of life and nature. Educational institution can invite experts to tell the mystery of the universe. Invite artists to share how to create shocking works, so as to obtain the opportunity of spiritual evolution. Secondly, attempts should be made to construct a practical model of college students’ life education under the concept of awe, and carry out themed activities of “awe for life”. Guide college students to love life and reduce the possibility of depression; At the same time, we should pay attention to and explore the positive psychological power of students (Seligman et al., 2006) and adopt positive teaching methods, such as heuristic teaching and cooperative learning, to make students feel happy and a sense of achievement in class, so as to improve their psychological happiness, reduce their depression and live a better life.

Limitations of the Study and Future Directions

Despite the significant insights this study has offered into the mediating mechanisms and contextual factors affecting the relationship between awe and depression, several limitations merit recognition. Firstly, the study adopted a cross-sectional design, which, despite being based on previous theories and evidence, made it difficult to establish causal relationships between variables. To address this issue, future research can employ a longitudinal design or scenario-based experiments. Second, the cross-sectional design of the study does not allow for causal inferences. Future research must adopt longitudinal or experimental designs to confirm the causality among these variables. Third, we sampled from a convenience population in one university, and as such, findings may not be representative of the general college student population. All the data in this study were self-reported by college students. Although the common method bias is not significant, there may still be a social desirability effect, where college students tend to present themselves as psychologically healthy so that they may provide dishonest answers. To measure depression, future research can consider using operational diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (American Psychiatric Association & DSM-5 Task Force 2013; Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™, 5th ed, 2013), and future research could attempt to collect data from multiple sources of information.

Our findings shed light on the mechanisms of how college students’ awe might influence depression. The results showed that awe not only directly influenced depression but also indirectly influenced it through the mediating effects of future self-continuity and presence of meaning, both independently and sequentially. This suggests that college students are not only due to a reduction in negative factors but also because of an increase in positive factors and the enhancement of their ability to address their psychological problems. Positive psychology education should be integrated into daily education in schools, focusing on and tapping into students’ positive psychological strengths to enhance their psychological well-being, reduce depression, and live a fulfilling life.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, and the Research Funds of Civil Aviation University of China, No. 3122024012.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Yujing Tao, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The study protocol was reviewed by the Ethics Committee of the Civil Aviation University of China (Approval No. 2023, 017). Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study or their legal guardians.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Abramson, L. Y., Seligman, M. E., & Teasdale, J. D. (1978). Learned helplessness in humans: Critique and reformulation. Journal of Psychopathology and Clinical Science, 87(1), 49–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.87.1.49 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

American Psychiatric Association & DSM-5 Task Force (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5™. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bai Y., Maruskin L. A., Chen S., Gordon A. M., Stellar J. E. et al. (2017). Awe, the diminished self, and collective engagement: Universals and cultural variations in the small self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(2), 185–209. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bai Y., Ocampo J., Jin G., Chen S., Benet-Martinez V. et al. (2021). Awe, daily stress, and elevated life satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 837–860. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bamonti, P., Lombardi, S., Duberstein, P. R., King, D. A., & Van Orden, K. A. (2016). Spirituality attenuates the association between depression symptom severity and meaning in life. Aging and Mental Health, 20(5), 494–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1021752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., & Masicampo, E. J. (2010). Conscious thought is for facilitating social and cultural interactions: How mental simulations serve the animal-culture interface. Psychological Review, 117(3), 945–971. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019393. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Beck, A. T. (1967). Depression: Clinical, experimental and theoretical aspects. New York: Harper and Row. [Google Scholar]

Bernerth, J. B., & Aguinis, H. (2016). A critical review and best-practice recommendations for control variable usage. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carstensen, L. L. (1987). Age-related changes in social activity. In: Handbook of clinical gerontology (pp. 222–237). Oxford: Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

Chen Y., Liu X., Chiu D. T., Li Y., Mi B. et al. (2022). Problematic social media use and depressive outcomes among college students in China: Observational and experimental findings. Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 4937. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19094937. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chen, S. K., & Mongrain, M. (2021). Awe and the interconnected self. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 16(6), 770–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818808 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chirico, A., & Gaggioli, A. (2021). The potential role of awe for depression: Reassembling the puzzle. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 617715. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Conway, M. A., Singer, J. A., & Tagini, A. (2004). The self and autobiographical memory: Correspondence and coherence. Social Cognition, 22(5), 491–529. https://doi.org/10.1521/soco.22.5.491.50768 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dai, Y., Jiang, T., & Miao, M. (2022). Uncovering the effects of awe on meaning in life. Journal of Happiness Studies, 23(7), 3517–3529. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00559-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dunstan, D. A., Scott, N., & Todd, A. K. (2017). Screening for anxiety and depression: Reassessing the utility of the Zung scales. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 329. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1489-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Dyer, N. G., Hanges, P. J., & Hall, R. J. (2005). Applying multilevel confirmatory factor analysis techniques to the study of leadership. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(1), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2004.09.009 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ersner-Hershfield, H., Wimmer, G. E., & Knutson, B. (2009). Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsn042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Frankl, V. E. (1992). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. 4th ed. Boston: Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Goodwin R. D., Dierker L. C., Wu M., Galea S., Hoven C. W. et al. (2022). Trends in U.S. depression prevalence from 2015 to 2020: The widening treatment gap. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 63(5), 726–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.05.014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Halusic, M., & King, L. A. (2013). What makes life meaningful: Positive mood works in a pinch. In: The psychology of meaning (pp. 445–464). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14040-022 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2016). Does recognition of meaning in life confer resiliency to suicide ideation among community-residing older adults? A longitudinal investigation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(6), 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.08.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Herrman H., Patel V., Kieling C., Berk M., Buchweitz C. et al. (2022). Time for united action on depression: A lancet-world psychiatric association commission. Lancet, 399(10328), 957–1022. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02141-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ingram, R. E. (2003). Origins of cognitive vulnerability to depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 27(1), 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022590730752 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, P., & Zhang, Z. (2023). Self-esteem mediation of perceived social support and depression in university first-year students: A longitudinal study. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(5), 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2257076 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Keltner, D., & Haidt, J. (2003). Approaching awe, a moral, spiritual, and aesthetic emotion. Cognition and Emotion, 17(2), 297–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930302297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

King, L. A., & Hicks, J. A. (2021). The science of meaning in life. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 561–584. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-072420-122921. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Li, X., Shao, H., Lin, L., & Yang, J. L. (2023). Gender differences in the predictive effect of depression and aggression on suicide risk among first-year college students. Journal of Affective Disorders, 327(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.123. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lodi-Smith, J., Spain, S. M., Cologgi, K., & Roberts, B. W. (2017). Development of identity clarity and content in adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(5), 755–768. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Luo, L., Zou, R., Yang, D., & Yuan, J. (2023). Awe experience triggered by fighting against COVID-19 promotes prosociality through increased feeling of connectedness and empathy. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 18(6), 866–882. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2131607 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mai, X., Li, F., Wu, B., & Wu, J. (2023). Mindfulness and meaning in life: The mediating effect of self-concept clarity and coping self-efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(3), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2195708 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maryam Hedayati, M. A., & Mahmoud Khazaei, M. A. (2014). An investigation of the relationship between depression, meaning in life and adult hope. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 114, 598–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.12.753 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Monroy, M., & Keltner, D. (2023). Awe as a pathway to mental and physical health. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(2), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221094856. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Monzonís-Carda, I., Adelantado-Renau, M., Beltran-Valls, M. R., & Moliner-Urdiales, D. (2021). An examination of the association between risk of depression and academic performance according to weight status in adolescents: DADOS study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 290, 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Orth, U., Robins, R. W., Meier, L. L., & Conger, R. D. (2016). Refining the vulnerability model of low self-esteem and depression: Disentangling the effects of genuine self-esteem and narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110(1), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pan, X., & Jiang, T. (2023). Awe fosters global self-continuity: The mediating effect of global processing and narrative. Emotion, 23(6), 1618–1632. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Paulos, H., & Kaiwen, X. (2019). Investigating the causes and treatments of hollow disease through a dialogue between finnish and chinese education. Theory and Practice of Psychological Counseling, 1(8), 329–372. https://doi.org/10.35534/tppc.0108025 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Santo, J. B., Martin-Storey, A., Recchia, H., & Bukowski, W. M. (2018). Self-continuity moderates the association between peer victimization and depressed affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(4), 875–887. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12372. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Schaffer, V., Huckstepp, T., & Kannis-Dymand, L. (2024). Awe: A systematic review within a cognitive behavioural framework and proposed cognitive behavioural model of awe. International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology, 9(1), 101–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41042-023-00116-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Schneider, K. J. (2009). Awakening to awe: Personal stories of profound transformation. Jason Aronson. [Google Scholar]

Schwarz, N. (2001). Feelings as information: Implications for affective influences on information processing. In Theories of mood and cognition: A user’s guidebook (pp. 159–176). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

Seligman, M. E. P., Rashid, T., & Parks, A. C. (2006). Positive psychotherapy. American Psychologist, 61(8), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.61.8.774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & John, O. P. (2006). Positive emotion dispositions differentially associated with Big Five personality and attachment style. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(2), 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510833 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shiota, M. N., Keltner, D., & Mossman, A. (2007). The nature of awe: Elicitors, appraisals, and effects on self-concept. Cognition and Emotion, 21(5), 944–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930600923668 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2016). The relationship between continuous identity disturbances, negative mood, and suicidal ideation. In: The primary care companion for CNS disorders (p. 18). https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.15m01824 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sokol, Y., & Serper, M. (2020). Development and validation of a future self-continuity questionnaire: A preliminary report. Journal of Personality Assessment, 102(5), 677–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1611588. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Steger, M., Frazier, P., Oishi, S., & Kaler, M. (2006). The meaning in life questionnaire: Assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Steger, M. F., Kashdan, T. B., Sullivan, B. A., & Lorentz, D. (2008). Understanding the search for meaning in life: Personality, cognitive style, and the dynamic between seeking and experiencing meaning. Journal of Personality, 76(2), 199–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00484.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Stellar, J. E. (2021). Awe helps us remember why it is important to forget the self. Ann N Y Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1501(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.14577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sundararajan, L. (2002). Religious awe: Potential contributions of negative theology to psychology, positive or otherwise. Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 22(2), 174–197. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0091221 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Terrell, K. R., Stanton, B. R., Hamadi, H. Y., Merten, J. W., & Quinn, N. (2024). Exploring life stressors, depression, and coping strategies in college students. Journal of American College Health, 72(3), 923–932. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2022.2061311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Vohs, K. D., & Schmeichel, B. J. (2003). Self-regulation and the extended now: Controlling the self alters the subjective experience of time. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2), 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.217. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Weger, U., & Wagemann, J. (2021). Towards a conceptual clarification of awe and wonder. Current Psychology, 40(3), 1386–1401. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-0057-7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xue L., Yan Y., Fan H., Zhang L., Wang S., Chen L. (2023). Future self-continuity and depression among college students: The role of presence of meaning and perceived social support. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 95(7), 1463–1477. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12219. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zung, W. W. (1965). A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry, 12(1), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools