Open Access

Open Access

Shyness and problematic social media use among Chinese adolescents: The mediating role of psychological insecurity and the moderating role of relational-interdependent self-constructs

1 School of Psychology, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, 321004, China

2 Intelligent Laboratory of Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Crisis Intervention of Zhejiang Province, Jinhua, 321004, China

3 Key Laboratory of Intelligent Education Technology and Application of Zhejiang Province, Jinhua, 321004, China

* Corresponding Author: Jianyong Chen. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 143-150. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065772

Received 12 June 2024; Accepted 28 December 2024; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

While the relation between shyness and problematic social media use (PSMU) among adolescents has been established, the mediating and moderating mechanisms underlying this association remain largely unexplored. The present study examined whether psychological insecurity mediated the association between shyness and adolescents’ PSMU and whether this mediation was moderated by relational-interdependent self-construal (RISC). A total of 1506 Chinese adolescents (Mage = 13.74 years, SD = 0.98) filled out self-report measures of shyness, psychological insecurity, RISC, and PSMU. SPSS (version 23.0) and the PROCESS macro (version 4.1) were employed to test the proposed model. Mediation analyses indicated that psychological insecurity mediated the association between shyness and adolescent PSMU. Furthermore, moderated mediation tests revealed that RISC moderated the first half of the mediation path, whereby RISC ameliorated the detrimental effects of shyness on psychological insecurity, consequently reducing the risk of PSMU. The present study provides further evidence on the mediating and moderating mechanisms between shyness and PSMU, which has important implications for the prevention and intervention of PSMU. For adolescents who exhibited pronounced shyness and low levels of RISC, a promising strategy for mitigating their PSMU would be interventions designed to cultivate social skills, alleviate psychological insecurity, and enhance their RISC.Keywords

Frequent use of social media may lead to problematic social media use in some adolescents. Problematic social media use (PSMU) refers to a phenomenon where individuals lose control over their usage behavior due to prolonged and intense use of social media, leading to negative physiological and psychological consequences (Blackwell et al., 2017). Adolescents who exhibit more severe PSMU are more likely to experience problems such as decreased academic performance (Homaid, 2022), anxiety (Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021), depression (Lopes et al., 2022), and sleep disorders (Tandon et al., 2020). In the Chinese context, social media (e.g., WeChat, TikTok, and Weibo) has become an indispensable part of adolescents’ lives. For instance, as of the end of 2023, the number of underage internet users (aged 6–18) in China reached 193 million (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2023). Among them, the proportion of those who frequently chat online and use social networking sites is 53.6% and 34.2%, respectively. Additionally, 13.1% of adolescents spend an average of more than 5 h online per day during holidays (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2023). Few studies have examined the risk factors for PSMU among developing country adolescents; hence this study aimed to explore the association of shyness with PSMU in Chinese adolescents and the role of psychological insecurity and relational-interdependent self-construal in that relationship.

Shyness and problematic social media use

Shyness has consistently been linked to adolescents’ social media use (Appel & Gnambs, 2019). Shyness, as a personality trait, refers to a certain discomfort or inhibition in social environments (Henderson & Zimbardo, 2001). In social situations, individuals who are shy often exhibit a fear of negative evaluation, accompanied by emotional distress (Henderson & Zimbardo, 2001). Despite their desire for social interaction, shy individuals fear and avoid real social situations, making it difficult for them to establish face-to-face interactions (Ang et al., 2018). Consequently, their interpersonal needs in real-life situations may not be fulfilled.

The uses and gratifications theory (Suler, 1999) posits that certain functions of the internet (e.g., anonymous text-only communication) can fulfill specific needs (e.g., the need for relationships) of individuals. Online social interactions may have a disinhibition effect by their invisibility and anonymity (Nesi et al., 2018; Saunders & Chester, 2008; Suler, 2004). By engaging in online communication frequently via social media, shy individuals can express themselves more freely, risking PSMU. This would be true of shy adolescents (Chen et al., 2021; Li et al., 2024). However, little is known about whether and how shyness has an association with PSMU among adolescents.

The mediating role of psychological insecurity

Psychological insecurity refers to a heightened perception of potential physical or psychological dangers and risks, along with the individual’s sense of powerlessness in coping with these events (Cong & An, 2004). Individuals with high levels of psychological insecurity often perceive life as filled with uncertainty and uncontrollability, experience feelings of unsafety during interpersonal interactions, and are more prone to heightened feelings of social rejection (Li et al., 2018a). Particularly, those with a higher shyness predisposition are vulnerable to a sense of insecurity (Gao et al., 2019; Geng et al., 2021; Li et al., 2022; Zhao et al., 2020). Psychological security is widely recognized as an essential human need that motivates individuals to continuously strive to attain and preserve it (Feng et al., 2023; Maslow, 1942). Therefore, individuals lacking a sense of security may employ specific strategies such as using the internet or social media, rather than engaging in face-to-face social interactions, to fulfill their psychological security (Jia et al., 2017, 2018). Consistent with these views, adolescents with a lower sense of security had a higher risk of PIU (Jia et al., 2017), PSU (Zhang et al., 2018) and PSMU (Feng et al., 2023). However, it remains unclear how shyness is associated with adolescent PSMU via the mediating role of psychological insecurity.

The moderating role of relational-interdependent self-construal

Relational-interdependent self-construal (RISC) refers to defining the self-construal in terms of relationships with others (Chang, 2015). Individuals with high RISC tend to define themselves based on their relationships with others, emphasizing their connections with others, and are more inclined to consider the ideas of others; whereas individuals with lower levels of RISC prefer to define themselves independently, emphasizing their separation from others, and are more inclined to consider their own ideas (Li et al., 2018b).

Especially in China guided by collectivist culture, individuals tend to define themselves through relationships, striving to maintain harmonious interpersonal connections (Heintzelman & Bacon, 2015; Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Shy Chinese adolescents with high RISC may experience less psychological insecurity due to receiving more social support, thereby lowering the likelihood of engaging in PSMU. We would not identify a study that examined RISC as a moderating variable in the relationship between shyness and psychological insecurity. However, a previous study reported that high RISC buffered the adverse effect of interpersonal alienation on excessive internet fiction reading through parasocial relationship (Yang et al., 2023). Building upon the above theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence, the present study proposed that RISC would moderate the mediated path between shyness and PSMU via psychological insecurity.

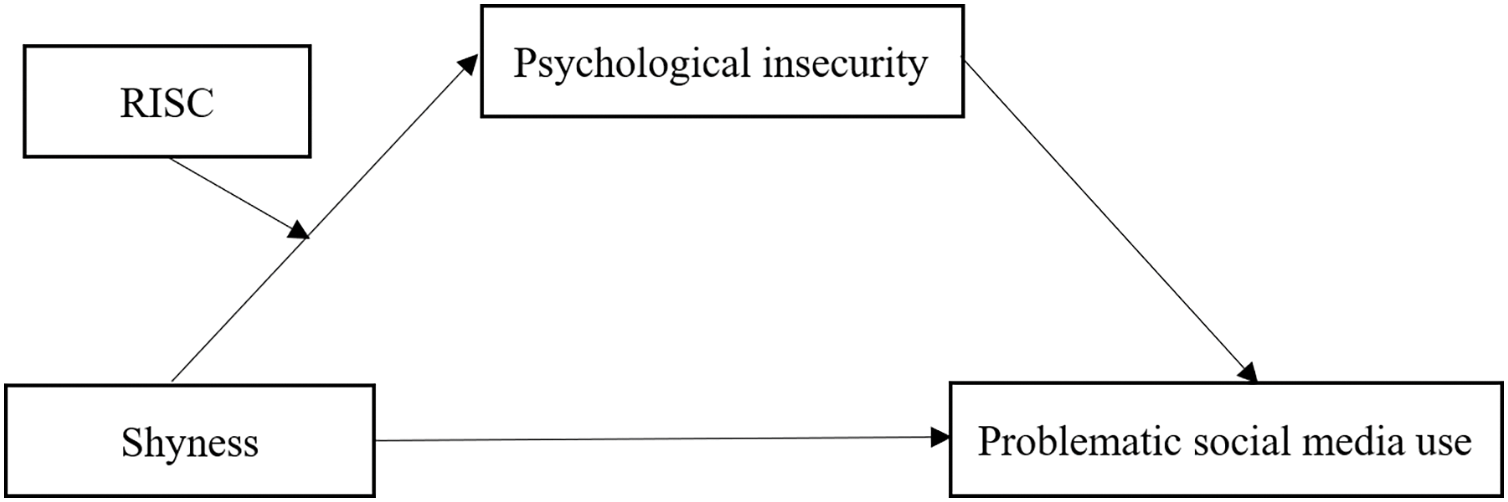

Based on previous theoretical and empirical evidence, the present study constructed a moderated mediation model (see Figure 1), which aimed to examine the effects of shyness on adolescents’ PSMU and its internal mechanisms by exploring the mediating role of psychological insecurity and the moderating role of RISC. We tested the following specific hypotheses:

Figure 1. Hypothesized theoretical model

Hypothesis 1. Shyness is higher among adolescents with greater PSMU.

Hypothesis 2. Heightened shyness is associated with higher psychological insecurity, which in turn predicts increased adolescent PSMU.

Hypothesis 3. High RISC buffers the harmful effect of shyness on adolescents’ psychological insecurity.

Participants were 1506 students from a junior high school in Zhejiang Province, China (females = 49.2%; M = 13.74 years, SD = 0.98 year). Regarding grade level distribution, there were 599 students in Grade 7 (39.8%), 459 students in Grade 8 (30.5%), and 448 students in Grade 9 (29.7%). The age of the participants ranged from 11 to 17 years old. In terms of socioeconomic status, 43 participants (2.9%) reported coming from affluent families, 1410 participants (93.6%) reported coming from middle-income families, and 53 participants (3.5%) reported coming from impoverished families.

The Chinese version of the Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (CBSS) was used to assess the level of shyness among individuals (Crozier, 2005; Xiang et al., 2018). The scale comprises 13 items (e.g., “I feel inhibited in social situations”) rated on a 5-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”), with higher scores indicating higher levels of shyness. The scale exhibited satisfactory internal consistency within the Chinese adolescents (Cronbach’s α = 0.88; Xiang et al., 2018). The Cronbach’s α for CBSS scores in the current study was 0.85.

Psychological insecurity was measured using the Insecurity Questionnaire (IQ), which was developed by Cong and An (2004). The scale consists of 16 items, including the dimensions of interpersonal security (8 items, e.g., “I am afraid of developing and sustaining close relationships with others”) and certainty of control (8 items, e.g., “I feel powerless to cope with and handle unexpected dangers in life”). The scale is scored on a 5-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”). Mean scores of all items were used in the analysis of results, with higher scores indicating a higher level of psychological insecurity felt by the individual. The reliability and validity of this questionnaire have been established in studies conducted with Chinese adolescents (Feng et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018a). Scores from the IQ showed a high level of internal consistency among Chinese adolescents (Cronbach’s α = 0.80; Cong & An, 2004). The Cronbach’s α for IQ scores in present study was 0.91.

Relational-interdependent self-construal

The Chinese version of the Relational-Interdependent Self-Construal Scale (RISCS, Cross et al., 2000; Huang & Bi, 2012) comprises 9 items (e.g., “My close relationships are an important reflection of ‘who I am’”) rated on a 5-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree” to 5 = “strongly agree”). Mean scores were utilized in the data analysis, with higher scores indicating higher levels of RISC. The RISCS scores showed high internal consistency among Chinese adolescents (Cronbach’s α = 0.80; Huang & Bi, 2012). In the present study, the Cronbach’s α for RISCS scores was 0.86.

Problematic social media use (PSMU)

The Problematic Social Media Use Scale (PSMUS) for Chinese Adolescents developed by Jiang (2018) consists of 20 items (e.g., “I often feel anxious or uneasy when unable to check my social media messages”), including five dimensions: increased stickiness (5 items), physical impairment (5 items), omission anxiety (4 items), cognitive failure (4 items), and guilt (2 items). The scale is scored on a 5-point scale (1 = “strongly disagree”; 5 = “strongly agree”). Mean scores were used for data analysis, with higher scores indicating more problematic social media use by the adolescents. The internal consistency of PSMUS scores among Chinese adolescents was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 0.91; Jiang, 2018). In this study, the Cronbach’s α for PSMUS scores was 0.92.

The present study obtained ethical approval from the university’s ethics board (Project No. ZSRT2022014). The parents or legal guardians provided consent for the students to take part in the study. The students individually assented to the study with assurances of anonymity and confidentiality and the right to withdraw at any time without penalty. To be eligible to participate, adolescents should use social media at least once per week and maintain at least one active social media account for a minimum of one year (Savci et al., 2022). The survey was conducted in a quiet classroom setting. Prior to the study, participants were provided with an explanation of the research purposes and clarified that the data would be used solely for scientific purposes. The students completed self-reported paper questionnaires, and the entire process took approximately twenty minutes.

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 software. First, we assessed potential common method bias that may arise from using self-report questionnaires in this study. Second, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were conducted for the study variables. To examine the mediating role of psychological insecurity in the relationship between shyness and adolescent PSMU, we utilized model 4 from Hayes’ SPSS PROCESS macro. Next, the moderating role of relational-interdependent self-construal in the relationship between shyness and psychological insecurity was examined using PROCESS model 7. The PROCESS macro provided 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the indirect effects of Model 4 and Model 7 based on 5000 bootstrap samples. It is generally considered that when the 95% CI does not include zero, the effect is significant. Gender, age, and socioeconomic status were included as control variables in the above analysis.

Harman’s single-factor analysis was used to test for potential common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003). The results showed that there were nine factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, of which the first factor explained 22.14% (<40%) of the variance, and thus there was no serious common method bias in this study.

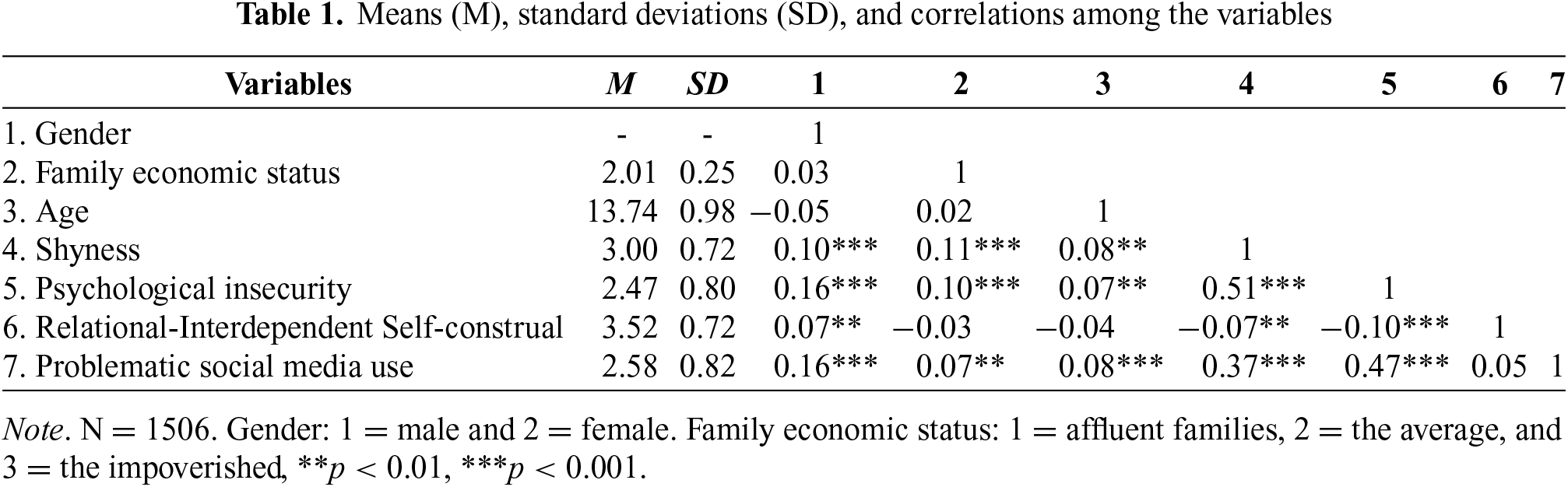

The results of correlation analysis (see Table 1) indicated that shyness was significantly positively correlated with psychological insecurity and PSMU, and significantly negatively correlated with relational-interdependent self-construal. Psychological insecurity was significantly negatively correlated with relational-interdependent self-construal and significantly positively correlated with PSMU.

Shyness significantly and positively predicted PSMU (β = 0.40, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.35, 0.45]) after controlling for covariates. Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was supported.

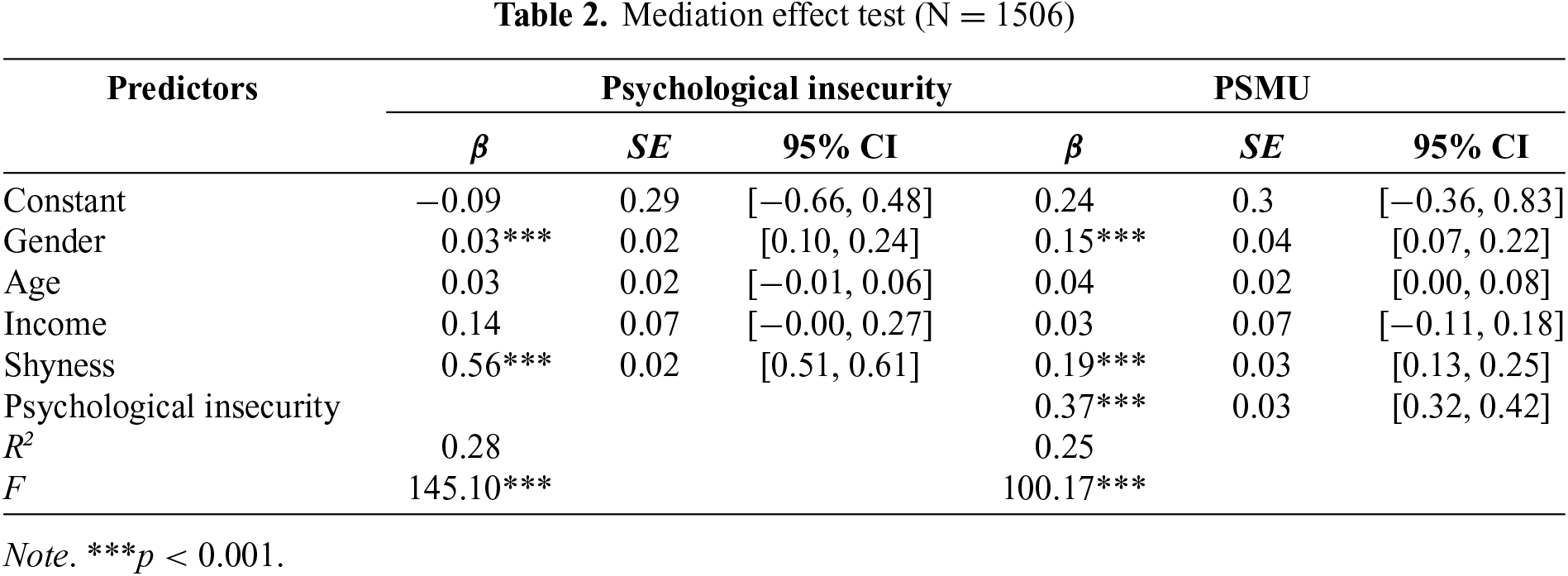

Testing for the mediating role of psychological insecurity

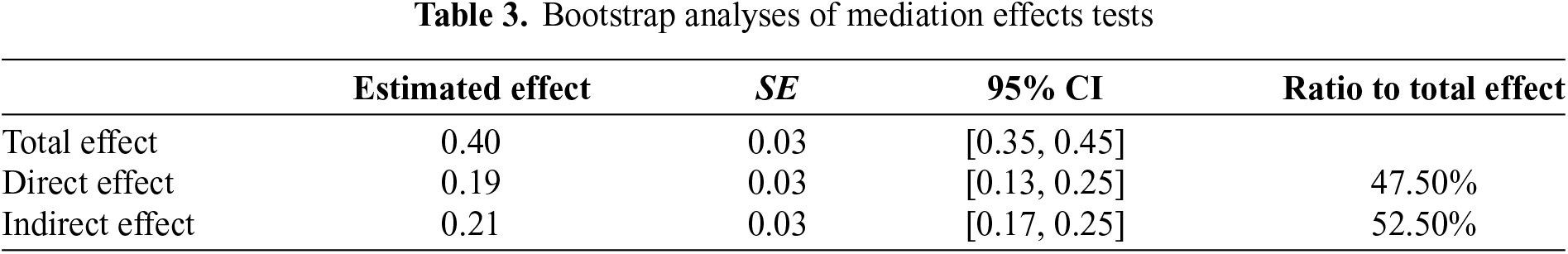

Shyness significantly positively predicted psychological insecurity (β = 0.56, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.51, 0.61]) (see Table 2). And psychological insecurity significantly positively predicted adolescent PSMU (β = 0.37, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.32, 0.42]). When the mediator and covariates simultaneously entered the regression model, the direct predictive effect of shyness on PSMU remained significant (β = 0.19, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.13, 0.25]), indicating that psychological insecurity partially mediated the relationship between shyness and PSMU. The proportion of the total effect explained by the mediation effect was 52.50% (see Table 3). Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

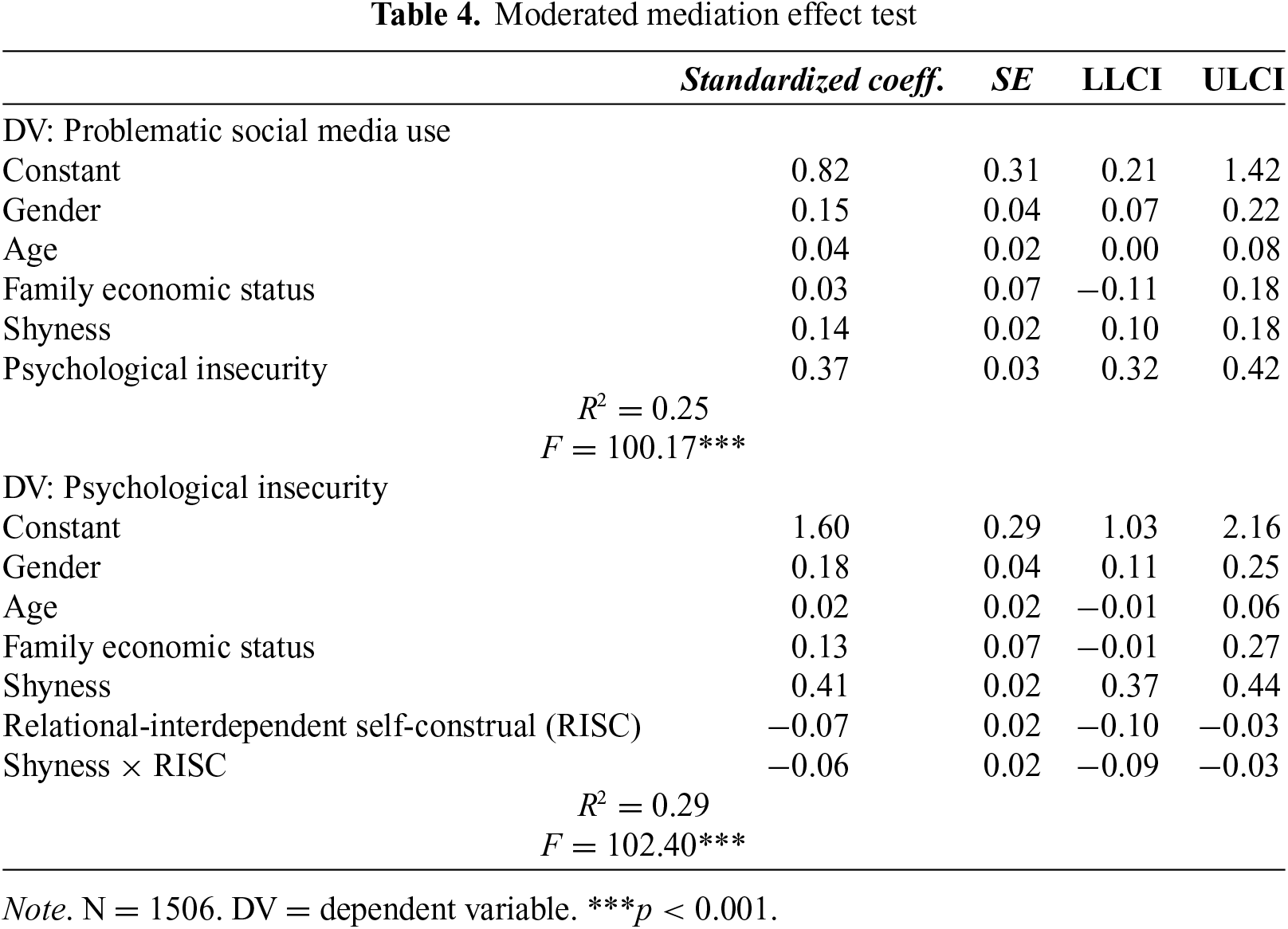

Testing for moderated mediation

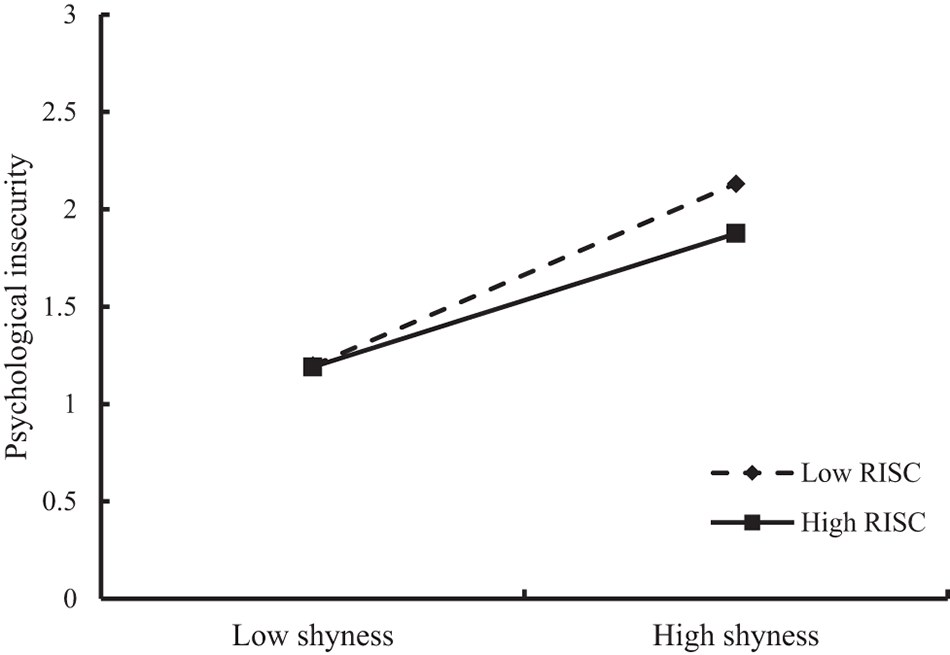

As shown in Table 4, it is evident that after controlling for covariates, the interaction between shyness and relational-interdependent self-construal (RISC) significantly predicted psychological insecurity (β = −0.06, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [−0.09, −0.03]). To elucidate how RISC moderates the relationship between shyness and psychological insecurity, simple slope tests were conducted by grouping RISC into high and low categories based on M ± 1 SD, as shown in Figure 2. The results indicated that for adolescents with lower levels of relational-interdependent self-construal (1 SD below the mean), shyness significantly predicted psychological insecurity (βsimple = 0.47, SE = 0.03, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.42, 0.52]). However, for adolescents with higher levels of relational-interdependent self-construal (1SD above the mean), the adverse effect of shyness on psychological insecurity was much weaker (βsimple = 0.34, SE = 0.02, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.30, 0.39]). Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

Figure 2. Conditional effect of psychological insecurity as a function of shyness and relational-interdependent self-construal

In summary, the mediating process through which shyness influences adolescent PSMU via psychological insecurity was moderated by RISC. In addition, conditional indirect effects analysis was conducted on 5000 bootstrap samples to examine the significance of indirect effects at different levels of relational-interdependent self-construal. Results revealed that compared to adolescents with lower levels of RISC (conditional indirect effect = 0.17, SE = 0.02, 95% CI = [0.14, 0.21]), the indirect effect of shyness on PSMU via psychological insecurity was weaker for adolescents with higher levels of RISC (conditional indirect effect = 0.13, SE = 0.01, 95% CI = [0.10, 0.16]).

The present study explored the effect of shyness on PSMU, and examined the role of psychological insecurity as well as relational-interdependent self-construal. The findings indicated that shyness was significantly associated with adolescent PSMU, and this relationship was mediated by psychological insecurity. Furthermore, RISC moderated the relation between shyness and psychological insecurity. The results strengthened our comprehension of adolescent PSMU by elucidating the intricate risk and protective factors.

Associations of shyness with adolescent problematic social media use

We found that shyness significantly and positively predicted PSMU among adolescents. This finding is in accordance with previous studies, which suggested that shyness exerted a detrimental effect on adolescent PIU (Li et al., 2024) and PSU (Chen et al., 2021). Also, the result of this study supports the uses and gratifications theory (Suler, 1999), which posits that certain characteristics of the Internet (e.g., anonymous text-only communication) drive individuals to satisfy unmet interpersonal needs through consistent Internet use. Additionally, this result provides empirical evidence for the online disinhibition effect, suggesting that engaging in online social interactions facilitated by invisibility and anonymity through the internet and social media platforms can promote disinhibition and have a strong appeal for shy adolescents (Saunders & Chester, 2008; Suler, 2004). Adolescents with higher levels of shyness tend to perceive themselves as performing poorly in real-life social environments, making negative evaluations of their social abilities (Ang et al., 2018). They may even experience fear and anxiety in social situations, leading to behavioral inhibition and social avoidance (Henderson & Zimbardo, 2001). Consequently, their social needs remain unfulfilled (Chen et al., 2021). For them, social media possesses features like cue absence, asynchronicity and convenience, making it perceived as a safe, controllable, and predictable social platform (Nesi et al., 2018). Consequently, shy adolescents may continuously turn to social media to express freely, fulfill their social needs, ultimately leading to PSMU.

The mediating role of psychological insecurity

The current study found that shyness positively predicted psychological insecurity, meaning that the higher the level of shyness, the stronger the psychological insecurity among adolescents. This finding is consistent with previous findings (Geng et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2020). Our result aligns with the social fitness model (Henderson & Zimbardo, 1999), which posits that shy individuals tend to anticipate poor social outcomes and harbor concerns about their performance and social competence when engaging in social interactions. They tend to perceive themselves as incapable of handling events in social situations, and lack certainty and a sense of control over external risks (Geng et al., 2021). Thus, shy individuals experience lower levels of psychological security. Furthermore, our findings indicated that adolescents’ psychological insecurity increases their vulnerability to PSMU. This finding is consistent with previous research, demonstrating that adolescents with higher levels of psychological insecurity were more likely to engage in PIU (Jia et al., 2018), PSU (Zhang et al., 2018), and PSMU (Feng et al., 2023). Consequently, psychological insecurity functions both as a consequence of shyness and a triggering factor for PSMU among adolescents.

Moreover, we found that psychological insecurity mediated the relationship between shyness and PSMU among adolescents. This result is consistent with findings in the realm of problematic behaviors (Jia et al., 2018; Zhao et al., 2020). Specifically, when adolescents had higher levels of shyness, their psychological insecurity increased, which in turn led to aggressive behaviors (Zhao et al., 2020). The finding of this study further corroborates the cognitive-affective processing system model (Mischel, 2004), which asserts that personality traits indirectly shape individuals’ behaviors through a network of cognitive and affective mediating mechanisms. In our study, shyness, as a personality trait, indirectly influenced adolescents’ PSMU behaviors through psychological insecurity. To sum up, shy adolescents may experience increased sense of psychological insecurity. In order to fulfill their sense of security, adolescents may indulge in social media use, and develop PSMU.

The moderating role of relational-interdependent self-construal

The result of this study indicated that RISC moderated the first link of the mediational chain of psychological insecurity between shyness and PSMU. Specifically, compared to individuals with low RISC, the adverse effect of shyness on psychological insecurity was reduced for adolescents with high RISC. Our finding supports the social psychological model of self-construal (Cross et al., 2000, 2002). Individuals with high levels of RISC tend to define themselves through their relationships with others and are more attuned to considering others’ perspectives. They are motivated to seek ways to integrate with others, aspiring to foster positive interpersonal relationships within their social networks (Cross et al., 2000, 2002). Such social relationships can provide a sense of feeling accepted and proper coping strategies, which may mitigate negative affective experiences (Li et al., 2018a). In the context of Chinese culture, individuals with higher RISC are more inclined to prioritize the establishment of harmonious interpersonal relationships (Markus & Kitayama, 1991). Therefore, they are more likely to receive supportive resources and feel connected, thereby alleviating negative emotions (Li et al., 2018a). Hence, for shy Chinese adolescents with high RISC, they may receive more emotional support, guidance and effective coping approaches, which serve as a buffer against the negative effects of shyness on their psychological insecurity, thereby reducing the risk of engaging in PSMU. This study is one of the few studies to examine the moderating role of RISC in the mediation link from shyness to PSMU via psychological insecurity, thus enriching the understanding of the mechanisms through which shyness influences PSMU.

Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of this study hold valuable implications. Theoretically, this study provides the evidence on psychological insecurity as an underlying mediating mechanism to establish the connection from shyness to a specific type of PIU (i.e., PSMU). Additionally, our results demonstrated that RISC buffered the adverse effect of shyness on psychological insecurity, contributing to a better understanding of the social psychological model of self-construal (Cross et al., 2000), and highlighting the constructive function of RISC in the effect of shyness on PSMU through psychological insecurity among Chinese adolescents.

Given the tendency of social withdraw among shy individuals in social contexts, the findings highlight the importance of developing their social skills. For instance, teachers should closely monitor shy adolescents’ interpersonal dynamics (Jia et al., 2017). When necessary, organizing group activities and self-disclosure tasks can help enhance their social skills and foster positive peer relationships (Chen et al., 2021; Jia et al., 2017). Practitioners can use these strategies to alleviate the detrimental effects of shyness on adolescent PSMU. Furthermore, shy adolescents with lower RISC are particularly more likely to experience higher levels of psychological insecurity with a need to develop more rational belief systems for self-correction when facing social situations (Feng et al., 2023; Li et al., 2018a). For instance, they could train in positive self-statements like, “Although I lack the skills to build harmonious relationships in social situations, I believe that these skills can be improved and that I can take control of my own life.” rather than “I lack the ability to engage in social interactions, I am inadequate.” This may further reduce the influence of shyness on PSMU among adolescents.

Limitations and future directions

The study has several limitations. Firstly, the present study utilized a cross-sectional research design, which does not allow for the determination of causal relationships between variables. Future research could employ experimental and longitudinal research designs to precisely validate the causal relationships among variables. Secondly, our findings indicated that psychological insecurity partially mediated the relationship between shyness and PSMU among adolescents. This suggests that there may be other mediating variables involved, such as maladaptive cognitions (Li et al., 2024). Shy individuals tend to excessively exaggerate the advantages of social media, as it provides an alternative and controllable way of social interactions. Consequently, they may develop maladaptive cognitions towards social media (“Only through social media, can I establish new relationships and gain emotional support”) (Saunders & Chester, 2008), thereby increasing the risk of PSMU. Future research should incorporate other potential mediating variables (e.g., maladaptive cognitions) into the model, to better elucidate the mechanism through which shyness influences PSMU.

The study results indicate that shyness has both direct and indirect effects on adolescents’ PSMU, with the indirect effect mediated by psychological insecurity. The results also reveal that the relationship between shyness and psychological insecurity is moderated by RISC, whereby RISC buffers the negative impact of shyness on psychological insecurity. This study findings contribute to a better understanding of how shyness influences PSMU among Chinese adolescents by validating a moderated mediation model. The findings provide novel perspectives for the design of intervention and prevention strategies concerning PSMU among adolescents.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This study was supported by the Philosophy and Social Science Planning Project of Zhejiang Province, China (No. 20NDQN266YB).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xiang Shi, Ju Feng, Jianyong Chen; data collection: Ju Feng, Jianyong Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Xiang Shi, Ming Gong, Jianyong Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Xiang Shi, Yingxiu Chen, Jianyong Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Normal University in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Approval Number: ZSRT2022014). Before data collection, participants were informed of the scientific purpose of the study and their right to withdraw at any time. All participants provided their written informed consent, and parental/guardian consent was requested by mail.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was given to all participants in order to get their allowance for this study. Legal guardian consent was requested by mail.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ang, C. S., Chan, N. N., & Lee, C. S. (2018). Shyness, loneliness avoidance, and internet addiction: What are the relationships? The Journal of Psychology, 152(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2017.1399854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Appel, M., & Gnambs, T. (2019). Shyness and social media use: A meta-analytic summary of moderating and mediating effects. Computers in Human Behavior, 98(4), 294–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.04.018 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Blackwell, D., Leaman, C., Tramposch, R., Osborne, C., & Liss, M. (2017). Extraversion, neuroticism, attachment style and fear of missing out as predictors of social media use and addiction. Personality and Individual Differences, 116(1), 69–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.04.039 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chang, C. (2015). Self-construal and facebook activities: Exploring differences in social interaction orientation. Computers in Human Behavior, 53(6), 91–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.049 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, Y., Gao, Y., Li, H., Deng, Q., Sun, C. et al. (2021). Shyness and mobile phone dependency among adolescents: A moderated mediation model of basic psychological needs and family cohesion. Children and Youth Services Review, 130(4), 106239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2021.106239 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2023). The fifth edition of the national survey on internet usage among minors. Retrieved from: https://www.cnnic.cn/n4/2023/1225/c116-10908.html [Google Scholar]

Cong, Z., & An, L. (2004). Developing of security questionnaire and its reliability and validity. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 18(2), 97–99. https://doi.org/10.3321/j.issn:1000-6729.2004.02.010 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cross, S. E., Bacon, P. L., & Morris, M. L. (2000). The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 78(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.791 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cross, S. E., Morris, M. L., & Gore, J. S. (2002). Thinking about oneself and others: The relational-interdependent self-construal and social cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.3.399 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Crozier, W. R. (2005). Measuring shyness: Analysis of the revised cheek and buss shyness scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 38(8), 1947–1956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2004.12.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Feng, J., Chen, J., Jia, L., & Liu, G. (2023). Peer victimization and adolescent problematic social media use: The mediating role of psychological insecurity and the moderating role of family support. Addictive Behaviors, 144(2), 107721. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107721. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gao, F., Zhao, J., Yang, H., Xuan, Z., & Han, L. (2019). The effect of shyness on aggression: The mediating role of security and social comparison orientation. Psychological Exploration, 39(4), 358–362. [Google Scholar]

Geng, J., Lei, L., Han, L., & Gao, F. (2021). Shyness and depressive symptoms: A multiple mediation model involving core self-evaluations and sense of security. Journal of Affective Disorders, 286(2), 19–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: A versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. 2012. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Heintzelman, S. J., & Bacon, P. L. (2015). Relational self-construal moderates the effect of social support on life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.021 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Henderson, L., & Zimbardo, P. G. (1999). Commentary: Developmental outcomes and clinical perspectives. In Schmidt, L. A., & Schulkin, J. (Eds.), Extreme Fear and Shyness: Origins and Outcomes. Series in Affective Science. New York, NY, USA: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Henderson, L., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2001). Shyness as a clinical condition: The Stanford model. In Alden, L. E., & Cozier, W. R. (Eds.), International handbook of social anxiety: Concepts, research and interventions relating to the self and shyness (pp. 431–447). Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

Homaid, A. A. (2022). Problematic social media use and associated consequences on academic performance decrement during COVID-19. Addictive Behaviors, 132(1), 107370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107370. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Huang, L., & Bi, C. (2012). The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the relational-interdependent self-construal scale. Advances in Psychology, 4, 173–178. https://doi.org/10.12677/ap.2012.24027 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jia, J., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y. et al. (2017). Psychological security and deviant peer affiliation as mediators between teacher-student relationship and adolescent Internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 73(4), 345–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.03.063 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jia, J., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Wang, Y., Sun, W. et al. (2018). Peer victimization and adolescent Internet addiction: The mediating role of psychological security and the moderating role of teacher-student relationships. Computers in Human Behavior, 85, 116–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.042 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jiang, Y. (2018). Development of problematic mobile social media usage assessment questionnaire for adolescents. Psychology: Techniques and Applications, 6(10), 613–621. https://doi.org/10.16842/j.cnki.issn2095-5588.2018.10.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, L., Chen, Y., & Liu, Z. (2022). Shyness and self-disclosure among college students: The mediating role of psychological security and its gender difference. Current Psychology, 41(9), 6003–6013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01099-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., Li, D., Li, X., Zhou, Y., Sun, W. et al. (2018a). Cyber victimization and adolescent depression: The mediating role of psychological insecurity and the moderating role of perceived social support. Children and Youth Services Review, 94, 10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.09.027 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., Lu, G. Z., & Li, Y. (2018b). Self-focused attention and social anxiety: the role of fear of negative evaluation and relational-interdependent self-construal. Psychological Science, 41(5), 1261–1267. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20180535 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, D., Yu, J., & Zhao, L. (2024). Effect of shyness on internet addiction: A cross-lagged study mediated by peer relationships. Current Psychology, 43(6), 5527–5540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04743-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lopes, L. S., Valentini, J. P., Monteiro, T. H., Costacurta, M. C. D. F., Soares, L. O. N. et al. (2022). Problematic social media use and its relationship with depression or anxiety: A systematic review. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 25(11), 691–702. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2021.0300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Maslow, A. H. (1942). The dynamics of psychological security-insecurity. Character & Personality; A Quarterly For Psychodiagnostic & Allied Studies, 10(4), 331–344. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1942.tb01911.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. E. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real-life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119(2), 106949. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mischel, W. (2004). Toward an integrative science of the person. Annual Review of Psychology, 55(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.042902.130709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nesi, J., Choukas-Bradley, S., & Prinstein, M. J. (2018). Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: Part 1—A theoretical framework and application to dyadic peer relationships. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 21(3), 267–294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-018-0261-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Saunders, P. L., & Chester, A. (2008). Shyness and the internet: Social problem or panacea? Computers in Human Behavior, 24(6), 2649–2658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2008.03.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Savci, M., Akat, M., Ercengiz, M., Griffiths, M. D., & Aysan, F. (2022). Problematic social media use and social connectedness in adolescence: The mediating and moderating role of family life satisfaction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 20(4), 2086–2102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00410-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Suler, J. R. (1999). To get what you need: Healthy and pathological Internet use. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 2(51), 385–393. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.1999.2.385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321–328. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tandon, A., Kaur, P., Dhir, A., & Mäntymäki, M. (2020). Sleepless due to social media? Investigating problematic sleep due to social media and social media sleep hygiene. Computers in Human Behavior, 113(1), 106487. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106487 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Xiang, B. H., Ren, L. J., Zhou, Y., & Liu, J. S. (2018). Psychometric properties of cheek and buss shyness scale in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(2), 268–271. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.02.013 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, C., Zhou, Z., Gao, L., Lian, S., Zhai, S. et al. (2023). The impact of interpersonal alienation on excessive internet fiction reading: Analysis of parasocial relationship as a mediator and relational-interdependent self-construal as a moderator. Current Psychology, 42(23), 19824–19839. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02601-x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, X. F., Gao, F. Q., Geng, J. Y., Wang, Y. M., & Han, L. (2018). Social avoidance and distress and mobile phone addiction: A multiple mediating model. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 26(3), 494–497. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki.1005-3611.2018.03.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, J., Gao, F., Xu, Y., Sun, Y., & Han, L. (2020). The relationship between shyness and aggression: The multiple mediation of peer victimization and security and the moderation of parent-child attachment. Personality and Individual Differences, 156(3), 109733. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109733 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools