Open Access

Open Access

The role of psychological meaningfulness in the relationship between job complexity and work-family conflict among secondary school teachers in Nigeria

1 Department of Psychology, Faculty of the Social Sciences, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, 410001, Nigeria

2 Department of Psychology, Faculty of the Management and Social Sciences, Caritas University, Amorji-Nike, 400201, Nigeria

3 Social Sciences Department, Akanu Ibiam Federal Polytechnic, Unwana, 490003, Nigeria

4 Enugu State University of Science and Technology (ESUT), Enugu, PMB 01660, Nigeria

* Corresponding Author: Gabriel C. Kanu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065768

Received 02 August 2024; Accepted 30 November 2024; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

This study examined how psychological meaningfulness moderates job complexity and work-family conflict in Nigerian secondary school teachers. This study included 1694 teachers from 17 Nigerian secondary schools (female = 69.54%, mean age = 33.19, SD = 6.44 years). The participants completed the Work-family Conflict Scale, Job Complexity Scale, and Psychological Meaningfulness Scale. Study design was cross-sectional. Hayes PROCESS macro analysis results indicate a higher work-family conflict with job complexity among the secondary school teachers. While psychological meaningfulness was not associated with work-family conflict, it moderated the link between job complexity and work-family conflict in secondary school teachers such that a meaningful work endorsement is associated with lower employee’s work-life conflict. These findings point to the importance of job functions to quality of family life. The study findings also suggest a need for supporting psychological meaningfulness for healthy work related quality of family life based on balancing work and family role demands.Keywords

The meanings people hold about their life situations are important to the many life roles they are involved, including the world of work. Work-to-family role conflict is a risk to work lives and this may depend on the nature of jobs people do (Kinman et al., 2017). Risk for work-family role conflict is higher in situations where work demands encroach upon family life and vice versa (Jahan Priyanka et al., 2024; Li et al., 2021; Allen et al., 2014). Job demands such as high workload, complexity, time restrictions, and irregular schedules may impend the quality of work-family life and work productivity (Sajid et al., 2022; Erdamar, 2014; Felstead, et al., 2002). Job complexity refers to psychologically demanding occupations that necessitate utilising an employee’s resources to deal with the stress involved (Sacramento et al., 2013; Sung et al., 2017). Outcomes may be different among individuals by the meanings they impute to their life situations, and of which these relationships have not been examined among secondary school teachers in the developing country of Nigeria.

Work-Family Conflict and Job Demands

Research on the work-family balance of educators, particularly those in the teaching profession, reveals that the tension between being a teacher and fulfilling household responsibilities leads to occupational stress. Studies suggest that teachers with heavy workloads and bringing work home are vulnerable to work-family conflict (WFC) (Jahan Priyanka et al., 2024; Li et al., 2021). Family-work conflict (FWC) can also occur when teachers experience delays in their professional responsibilities due to domestic obligations (Alvarado & Bretones, 2018; Erdamar & Demirel, 2016). Job complexity demands high adaptability to work more quickly or alter their work habits (Ragu-Nathan et al., 2008), implementing new ways of executing tasks efficiently (Berg et al., 2010; Tims & Bakker, 2010). Job complexity is associated with a degree of uncertainty. In achieving work outcomes essential for a successful product (Wood, 1986), the complexities of jobs could be by their information demands and coordination needs (Hunter et al., 1990), less studied in Nigerian school settings.

Psychological Meaningfulness Moderation

Psychological meaningfulness (Rosso et al., 2010), is a person’s sense of self-worth and appreciation for life’s meaning and purpose, as well as how seriously they take their existence (Taubman-Ben-Ari & Weintroub, 2008). With sense of meaningful work, teachers may be better feelings and more energy for their families when they get home from work, and also about their jobs (Galinsky, 2005). There would be less friction between the demands of work and family if a job allows one to balance the needs of oneself and those of others by providing ample time and space for reflection (Unal, 2017). Thus, psychological meaningfulness can moderate school teachers’ job complexity, and work-family conflict. Work duties and activities that align with teachers’ self-concepts are associated with more psychologically meaningful working experiences, and lower risk for work-family conflict. When the sense of meaningfulness is the same in both personal and professional life, work-family balance improves, and work-family conflict decreases (Grady & McCarthy, 2008). In essence, meaningful work engenders a sense of control and energy conservation mitigates the risk of burnout resulting from occupational stressors.

Goal of the study: This study examined how psychological meaningfulness influence job complexity and work-family conflict among secondary school teachers in Nigeria. In this regard, we tested the following research hypotheses:

H1: Work–family conflict is higher with job complexity.

H2: Work–family conflict is lower with psychological meaningfulness.

H3: Psychological meaningfulness moderates the job complexity and work-family conflict for lower work family conflict.

This study involved a total of 1694 Nigerian secondary school teachers. Out of the total number of teachers, 516 (30.46%) were male, and 1178 (69.54%) were female. Among them, 1457 were married, 224 were single, and 13 were divorced. By educational qualifications, the teachers held mostly bachelor’s degrees (47.5%). A total of 1333 of the teachers (78.69%) were permanent staff.

Work-family conflict scale (Geurts et al., 2005)

The Work-Family Conflict (WFC) Scale, developed by Geurts et al. (2005), consists of nine items, five designed to capture strain-based interference and four to measure time-based interference. It is scores on a Likert-type scale (low = 1; higher = 4), with higher scores indicating greater levels of work-family conflict. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for scores from the WFC was 0.84 in the present study.

Job complexity scale (Shaw & Gupta, 2004)

The Job Complexity Scale, developed by Shaw and Gupta (2004), consists of three items adapted from Seashore et al. (1983) designed to measure the complexity of a job. It is scores on a 5-point Likert scale (low = 1; high = 5), with higher scores indicating greater levels of job complexity (α = 0.73). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for scores from the job complexity scale was 0.71 in the present study.

Psychological meaningfulness scale (May et al., 2004)

The Psychological Meaningfulness Scale developed by May et al. (2004) consists of six items that measures how meaningful work is to people. It is scores on a Likert scale (low = 1; high = 7), with higher scores indicating greater levels of psychological meaningfulness (α = 0.90). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for scores from the psychological meaningfulness scale was 0.88 in the present study.

The research ethics committee of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka approved the study. In addition, the school management granted study permission. Participants consented to the study with information on the purpose of the study. All procedures followed were under the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

The data were analysed using SPSS 23.0 software. Specifically, Regression-based PROCESS was utilized (Hayes, 2013).

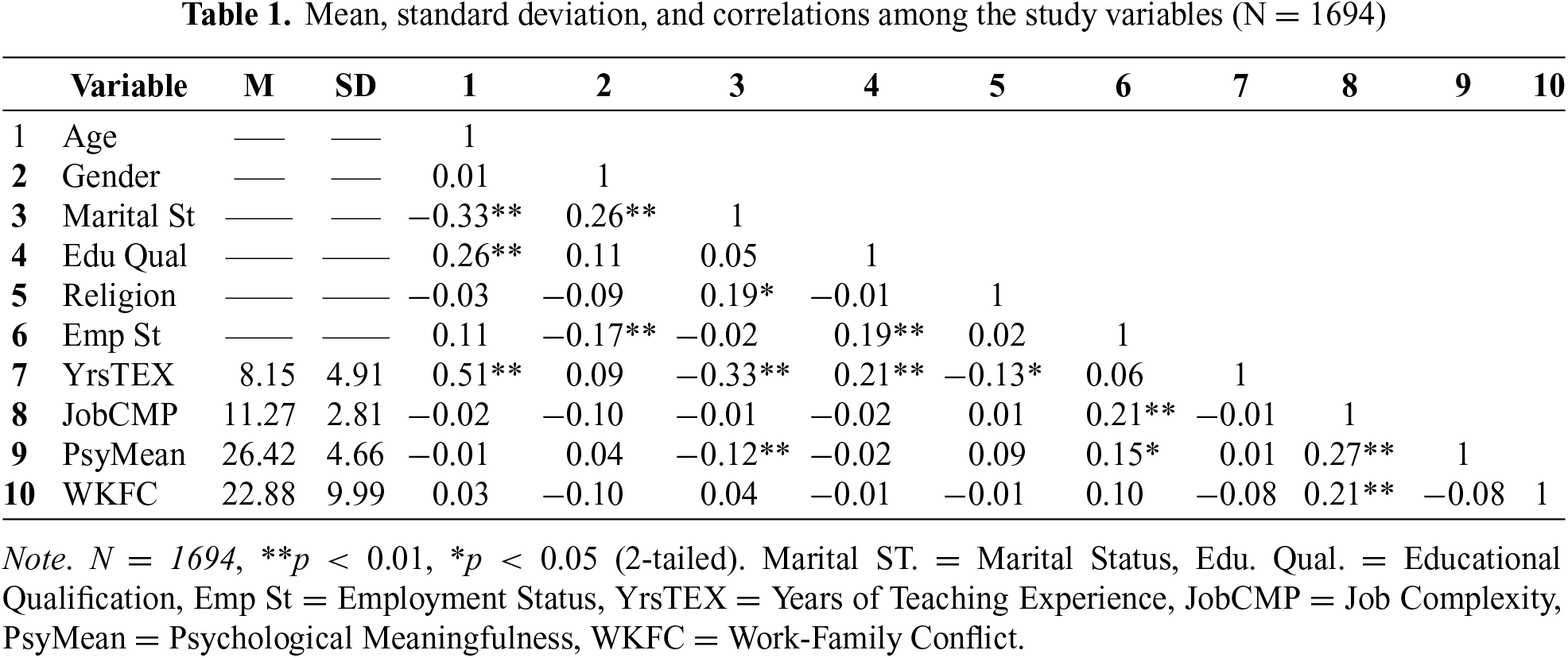

Descriptive Statistics: Table 1 presents the correlation analysis findings. The table indicates that age, gender, marital status, educational qualification, religion, employment status, and years of teaching experience were not statistically correlated with work-family conflict among secondary school teachers. Hence, they were excluded from the subsequent analysis. However, job complexity (r = 0.21, p < 0.01) was positively related with work-family conflict. The result showed that psychological meaningfulness (r = −0.08, p > 0.05) did not relate with work-family conflict. Also, age correlated with marital status (r = −0.33, p < 0.01), educational qualification (r = 0.26, p < 0.01), and years of teaching experience (r = 0.51, p < 0.01). Gender correlated with marital status (r = 0.26, p < 0.01) and employment status (r = −0.17, p < 0.01). There are also significant relationships between marital status and religion (r = 0.19, p < 0.05), years of teaching experience (−0.33, p < 0.01) and psychological meaningfulness (r = −0.12, p < 0.01). There are also significant correlations between educational qualification and employment status (r = 0.19, p < 0.01), educational qualification and years of teaching experience (r = 0.21, p < 0.01). Religion correlated with years of teaching experience (r = −0.13, p < 0.05). Also, employment status positively correlated with both job complexity (r = 0.21, p < 0.01) and psychological meaningfulness (r = 0.15, p < 0.05). There is also significant positive relationship between job complexity and psychological meaningfulness (r = −0.27, p < 0.01).

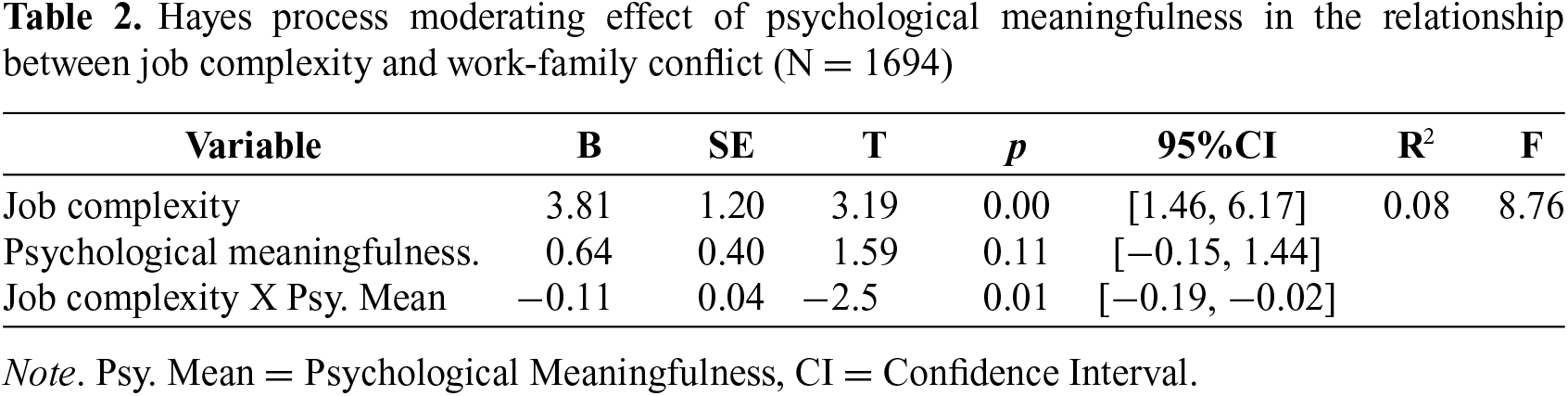

Work-family conflict and job complexity

The result of the analysis in Table 2 indicates that job complexity was associated with higher work-life conflict (β = 3.81, 95% CI [1.46, 6.17], p < 0.01) confirming hypothesis 1. Psychological meaningfulness was not associated with work-life conflict (β = 0.64, 95% CI [−0.15, 1.44], p > 0.05) not confirming hypothesis 2.

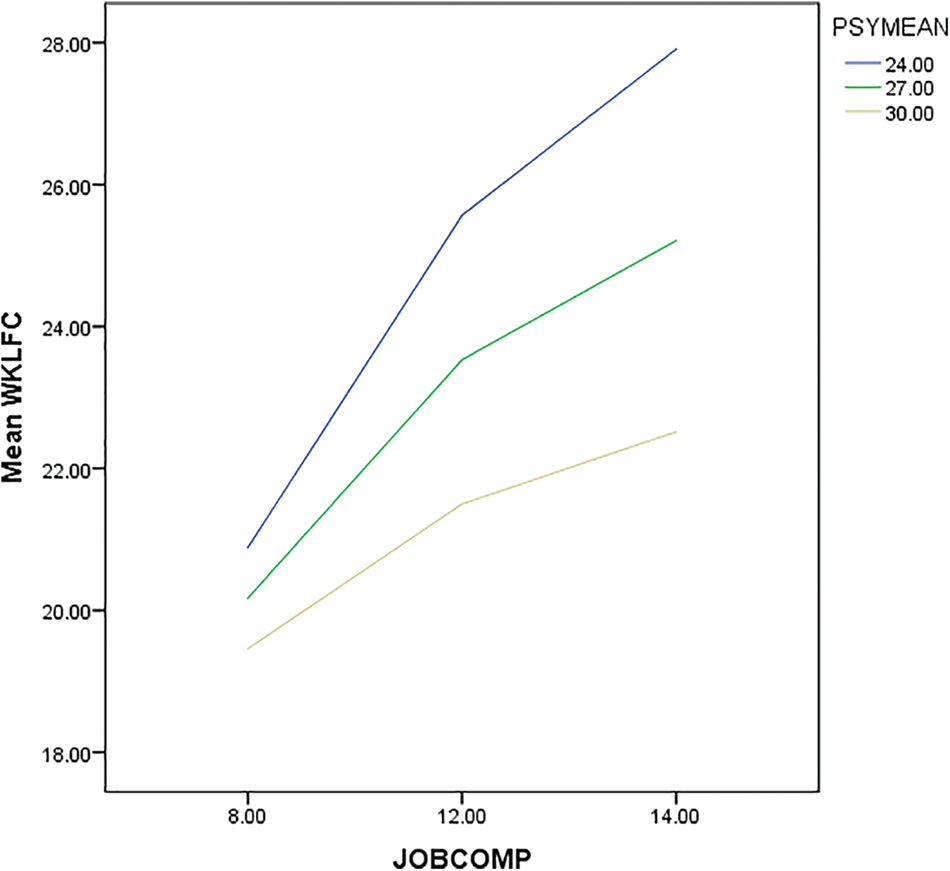

Psychological Meaningfulness Moderation: The interaction effect of psychological meaningfulness on the relationship between job complexity and work-family conflict among secondary school teachers was significant (β = −0.11, 95% CI [−0.19, −0.02], p < 0.01), to suggest that teachers have lower work-family conflict when they perceive their complex jobs to be meaningful (see Figure 1). This confirms hypothesis 3.

Figure 1. The moderating effect of psychological meaningfulness in the relationship between job complexity and work-family conflict among secondary school teachers. WKFC = Work-Family Conflict, JOBCOMP = Job Complexity, PSYMEAN = Psychological Meaningfulness.

The findings confirmed a positive relationship between job complexity and work-family conflict among secondary school teachers in Nigeria. Teachers, like other professionals, face challenges in balancing work-life and classroom responsibilities (Li et al., 2021; Toprak et al., 2022). Work-family conflict can harm families and workplaces, impacting overall productivity and performance (Naithani, 2010).

Psychological meaningfulness did not have a significant negative relationship with work-family conflict among secondary school teachers in Nigeria. Psychological meaningfulness in work can be understood as a subjective experience that signifies a person’s work matters and holds importance. Since this sense of meaningfulness is relative, other factors may play significant roles in both work and family domains to activate it (Fouché et al., 2017). As a result, many teachers may not be able to easily perceive the balance between their work and family lives.

Psychological meaningfulness moderated the relationship between job complexity and work-family conflict such that a teacher’s work-family conflict reduces even under tasking jobs. Employees who find their jobs meaningful are more inclined to tackle challenging tasks. By anticipating positive outcomes, individuals can motivate themselves to tackle tasks and achieve their goals, which ultimately improve their performance and family life (Sajid et al., 2022; Searle & Parker, 2013). This sense of purpose helps employees who face challenging tasks to integrate both their work and family roles more effectively.

WFC is more prevalent among teachers than other vocations and research shows that high school teachers have a greater level of work-family conflict, which may significantly affect their mental health and impair the quality of what they teach their pupils (Hu et al., 2019; Islam et al., 2019; Jan et al., 2022; Li et al., 2021). The International Labour Organization (ILO) states that work-life balance policies in low-income and middle-income countries are behind high-income countries, including Africa. In Nigeria, work-family conflict is a problem in secondary schools, where teachers have to deal with multiple roles and workload issues (Ademola et al., 2021; Ojo et al., 2014). Meaningful work is not only about the nature of the job but also how it aligns with personal values and principles. Engaging in meaningful work provides fulfilment and purpose, contributing to a sense of completeness in life. Sharing this essence and fulfilment with a partner leads to increased balance and reduced discord (Chalofsky, 2010). Teachers who perceive their work as being of greater significance are likely to experience a diminished intensity in the relationship between hindrance stressors and job burnout. A study by Van Wingerden and Poell (2019) found that individuals who view their job as meaningful display greater resilience, characterized by determination and adaptability.

Prior studies have indicated that enhancing teachers’ achievement can be achieved by alleviating stress, as psychological meaningfulness is a crucial factor for their success (Carlson et al., 2006; Sirgy et al., 2001). Teachers frequently engage in work that goes beyond their designated workplace, necessitating additional exertion even in their residences.

Limitations, Further Directions and Conclusions

This study has some limitations. The use of cross-sectional designs and self-report measures may make it difficult to establish causal relationships. To address these limitations, a longitudinal design study is needed. Also this implemented a few Nigerian schools, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future studies should extend this study to other schools across Nigeria to improve the external validity of the study for greater confidence in the findings.

The study has found that how an employee’s interprets their work can help manage the difficulties of being a teacher. To overcome these challenges, educators must strive to find greater significance and meaning in their work. Meaningful work can significantly impact both teachers and schools.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the management of the schools and their teachers that participated in the study.

Funding Statement: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contributions to the paper as follows: Initiation of the first draft and Introduction: Gabriel Kanu and Noah Adeji; Development, collection of data and data analysis: Tobias Obi; and Elom Omena; Interpretation of results and review of the draft: Raphael Anike and Alexander Amaechi. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were per the ethical standards of the institutional and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ademola, O. A., Tsotetsi, C., & Gbemisola, O. D. (2021). Work-life balance practices: Re-thinking teachers’ job performance in Nigeria secondary schools. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences and Humanities, 7(2), 102–114. [Google Scholar]

Allen, T. D., Cho, E., & Meier, L. L. (2014). Work–family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 1(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091330 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Alvarado, L., & Bretones, F. D. (2018). New working conditions and well-being of elementary teachers in Ecuador. Teaching and Teacher Education, 69(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.10.015 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Berg, J. M., Wrzesniewski, A., & Dutton, J. E. (2010). Perceiving and responding to challenges in job crafting at different ranks: When proactivity requires adaptivity. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 31(2–3), 158–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.645 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Carlson, D. S., Kacmar, K. M., Wayne, J. H., & Grzywacz, J. G. (2006). Measuring the positive side of the work–family interface: Development and validation of a work–family enrichment scale. Journal of Vocational Behaviour, 68(1), 131–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.02.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chalofsky, N. E. (2010). Meaningful workplaces: Reframing how and where we work. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Erdamar, G. (2014). Investigation of work-family, family-work conflict of the teachers. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4919–4924. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.1050 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Erdamar, G., & Demirel, H. (2016). Job and life satisfaction of teachers and the conflicts they experience at work and at home. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 4(6), 164–175. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i6.1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Felstead, A., Jewson, N., Phizacklea, A., & Walters, S. (2002). Opportunities to work at home in the context of work-life balance. Human Resource Management Journal, 12(1), 54–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-8583.2002.tb00057.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fouché, E., Rothmann, S., & Van der Vyver, C. (2017). Antecedents and outcomes of meaningful work among school teachers. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology/SA Tydskrif Vir Bedryfsielkunde, 43, a1398. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v43i0.1398 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Galinsky, E. (2005). Children’s perspectives of employed mothers and fathers: Closing the gap between public debates and research findings. In: D. F. Halpem, & S. E. Murphy (Eds.From work-family balance to work-family intervention. Changing the metaphor (pp. 219–237). London: Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

Geurts, S., Taris, T., Kompier, M., Dikkers, J., Van Hooff, M., et al. (2005). Work-home interaction from a work psychological perspective: Development and validation of a new questionnaire, the SWING. Work & Stress, 19, 319–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678370500410208 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grady, G., & McCarthy, A. M. (2008). Work-life integration: Experiences of mid-career professional working mothers. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(5), 599–622. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940810884559 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (vol. 1, no. 6, pp. 12–20). [Google Scholar]

Hu, H., Zhou, H., Mao, F., Geng, J., Zhang, L., et al. (2019). Influencing factors and improvement strategy to the quality of nursing work life: A review. Yangtze Medicine, 3(4), 253–260. [Google Scholar]

Hunter, J. E., Schmidt, F. L., & Judiesch, M. K. (1990). Individual differences in output variability as a function of job flexibility. Journal of Applied Psychology, 75, 28–45. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.1.28 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Islam, T., Ahmad, R., Ahmed, I., & Ahmer, Z. (2019). Police work-family nexus, work engagement and turnover intention: Moderating role of person-job-fit. Policing: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-09-2018-0138 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jahan Priyanka, T., Akter Mily, M., Asadujjaman, M., Arani, M., & Billal, M. M. (2024). Impacts of work-family role conflict on job and life satisfaction: A comparative study among doctors, engineers and university teachers. PSU Research Review, 8(1), 248–271. https://doi.org/10.1108/PRR-10-2021-0058 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jan, N. A., Raj, A. B., & Subramani, A. K. (2022). Does smart phone affect work-life balance, stress and satisfaction among teachers during online education? International Journal of Management in Education, 16(4), 438–462. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMIE.2022.123835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kinman, G., Clements, A., & Hart, J. A. (2017). Working conditions, work-life conflict and wellbeing in U.K. prison officers: The role of affective rumination and detachment. Criminal Justice and Behaviour, 44(2), 226–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816664923 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, X., Lin, X., Zhang, F., & Tian, Y. (2021). Playing roles in work and family: Effects of work/family conflicts on job and life satisfaction among junior high school teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 5998. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.772025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317904322915892 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Naithani, D. (2010). Recession and work-life balance initiatives. Romanian Economic Journal, 37, 55–68. [Google Scholar]

Ojo, I. S., Salau, O. P., & Falola, H. O. (2014). Work-life balance practices in Nigeria: A comparison of three sectors. Journal of Competitiveness, 6(2), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.7441/joc.2014.02.01 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ragu-Nathan, T. S., Tarafdar, M., Ragu-Nathan, B. S., & Tu, Q. (2008). The consequences of techno stress for end users in organizations: Conceptual development and empirical validation. Information Systems Research, 19(4), 417–433. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1070.0165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rosso, B. D., Dekas, K. H., & Wrzesniewski, A. (2010). On the meaning of work: A theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30(5), 91–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sacramento, C. A., Fay, D., & West, M. A. (2013). Workplace duties or opportunities? Challenge stressors, regulatory focus, and creativity. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 121(2), 141–157. [Google Scholar]

Sajid, S. M., Jamil, M., & Abbas, M. (2022). Impact of teachers’work-family conflict on the performance of their children. Jahan-e-Tahqeeq, 5(1), 229–239. [Google Scholar]

Searle, B. J., & Parker, S. K. (2013). Work design and happiness: An active, reciprocal perspective. In: S. A. David, I. Boniwell, & A. Conley Ayers (Eds.The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 1–21). New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199557257.013.0053 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Seashore, S. E., Lawler, E. E., Mirvis, P. H., & Cammann, C. (1983). Observing and measuring organizational change: A guide to field practice. New York: Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Shaw, J. D., & Gupta, N. (2004). Job complexity, performance, and well-being: When does supplies-values fit matter?. Personnel Psychology, 57(4), 847–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2004.00008.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sirgy, M. J., Efraty, D., Siegel, P., & Lee, D. -J. (2001). A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spill-over theories. Social Indicators Research, 55(3), 241–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010986923468 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sung, S. Y., Antefelt, A., & Choi, J. N. (2017). Dual effects of job complexity on proactive and responsive creativity: Moderating role of employee ambiguity tolerance. Group Organizational Management, 42(3), 388–418. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601115619081 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Taubman-Ben-Ari, O., & Weintroub, A. (2008). Meaning in life and personal growth among paediatric physicians and nurses. Death Studies, 32(7), 621–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180802215627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tims, M., & Bakker, A. B. (2010). Job crafting: Towards a new model of individual job redesign. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 36(2), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v36i2.841 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Toprak, M., Tösten, R., & Elçiçek, Z. (2022). Teacher stress and work-family conflict: Examining a moderation model of psychological capital. Irish Educational Studies, 43(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2022.2135564 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Unal, Z. M. (2017). The mediating role of meaningful work on the relationship between needs for meaning-based person-job fit and work-life conflict. In: International Scientific Conference on Sustainable Development Goals (pp. 332–338). [Google Scholar]

Van Wingerden, J., & Poell, R. F. (2019). Meaningful work and resilience among teachers: The mediating role of work engagement and job crafting. PLoS One, 14(9), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0222518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wood, R. E. (1986). Task complexity: Definition of the construct. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes, 37(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(86)90044-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools